DOWN WITH ELECTIONS!

Part 1 Part 2 Part 3 Part 4 Part 5 Part 6

PART 3

Examples of the Legislation in Action

How might all this work in practice? Let us consider some examples.

Example 1: The Passage of a Proposal by a Private Citizen

Suppose Bill Brown decides that Watchamacallit Bay is over-fished. He writes a letter to the Assembly:

Dear Sirs and Madams,

Watchamacallit Bay is hopelessly overfished, when I was a kid there was fish everywhere, now its DEAD!!! Theres no fish left!

Fishing should be banned in Watchamacallit Bay.

Yours etc, Bill Brown

He receives a reply in warm, friendly, bureaucratic style from the Proposals Committee:

Dear Sir/Madam,

Re: Proposal to ban fishing in Watchamacallit Bay.

The Proposals Committee has received your proposal, and thanks you for it.

Proposal Number: 2050/456789 (please quote this reference in correspondence)

Status of proposal: Pending. (You will be informed of changes to the status.)

Current Regulations in force concerning this matter, or which may be affected:

- Government of Sortitia:

- Fisheries Act 2021/143, amended 2025/392. This is available at http://www.gov_sortitia_leg.so/xxxxxxxxx

- Region of South-West Sortitia:

- Waterways Act 2028/39. This is available at http://www.gov_sw_sortitia_reg.so/yyyy

- Current proposals on related matters:

- Proposal 2049/3132: Amendment to Fisheries Act 2021/143.

- Details of this, including hearing dates if fixed, are available at http://www.gov_sortitia_props.so/zzzz

- Proposal 2048/203: Extension of Port Facilities at Watchamacallit Bay.

- Details of this, including hearing dates if fixed, are available at http://www.gov_sortitia_props.so/pqrpq

- Proposal 2047/1923: Proposed Watchamacallit Bay International Airport.

- Details of this, including hearing dates if fixed, are available at http://www.gov_sortitia_props.so/xyzxyz

This list may not be exhaustive. You are advised to check with regional and local government authorities for regulations and by-laws which may affect or be affected by your proposal.

Notes:

- Clarification required:

- Please advise if the proposal concerns all marine animal species, including teleosts, cartilaginous fish, shellfish and crustaceans.

- Please advise the exact geographical limits proposed.

- Please advise if both commercial and recreational fishing are affected, and which fishing methods are affected.

- Please advise if the proposed restriction is to be permanent, temporary, or seasonal, and the proposed time limits.

- Supporting information.

It is suggested that you send to the Proposals Committee any information or evidence which you have regarding the desirability of implementing this proposal.

Yours faithfully, etc

(Alternatively, if this is a matter for a state or regional government the Proposals Committee might refer Bill Brown to the Proposals Committee of that government.)

It may be that Bill Brown will take fright at this, and that nothing further is heard from him, in which case his proposal will languish as “pending” for ever. However, if Bill is serious, he will go away and do his homework. Perhaps there is a proposal pending or under review which includes or could include his idea, and he may choose to transfer his attention to this proposal.

If not, and he can produce evidence that his proposal is desirable and popular, (for example, studies of fish populations, simulations comparing the ecological and economic effects of his proposal with “business as usual” and a petition with a large number of signatures), and if he refines it to be more precise, then the Proposals Committee would send it to the legal draftsmen to be put in proper form.

Both the Proposals Committee and the professional draftsmen would check for incompatibility with or duplication of existing regulations or proposals at all levels of government. The first draft would be sent to Bill Brown, and published for all to see. The Proposals Committee would also forward it to the Agenda Committee with a list of any regulations or proposals which would need to be modified in order to implement Bill Brown’s proposal and a recommendation for the priority to be assigned to it.

In rare cases of urgency, the Agenda Committee might put the proposal on the agenda for immediate consideration by the Assembly. It might also send it back to the Proposals Committee for re-drafting if it judges that the proposal is not sufficiently clear or well-framed for intelligent consideration.

More often it would put on the agenda a motion to set up a Single-Issue Policy Committee (assuming that there is no existing Policy Committee whose mandate covers the issue) to study and report on the proposal within a given time. The SIPC would call for submissions from the general public, from recognised experts, and from government Ministries. After examining the submissions, the SIPC would refer it back to the Agenda Committee with its recommendations and its reasons for making them. These recommendations would include minority recommendations, and would take such forms as “in favour”, “against”, “amendment proposed” and “revision of wording necessary”. If the Agenda Committee, on the advice of the SIPC, considered amendment or re-wording to be necessary the proposal would go back to the Proposals Committee and the draftsmen. If the Agenda Committee considered the proposal sufficiently well-drafted it would then put it on the agenda to go before the Assembly, which could approve it (with or without amendments), reject it, or refer it back to the SIPC for further consideration or clarification.

If there is a unicameral Assembly, and if the proposal is passed, it now becomes law. If there is a second House or “Review Chamber” the proposal would pass to this chamber which could approve it, or return it to the first chamber for re-consideration, with proposed amendments. (The Review Chamber could not reject the proposal outright, nor refer it back more than twice.)

At all stages of this process the text of the proposal, with the various changes made or suggested would be available to the public on the government web site, and perhaps by printed media. This ensures that the actions of the Agenda Committee and the Proposals Committee would always be subject to scrutiny by the Assembly and the public.

Members of the Assembly would be free to propose a motion that a proposal be given immediate consideration, or that it be referred back to the SIPC, or if an SIPC does not exist, that one be constituted to study the proposal and report back with its recommendations.

In this example, it is likely that the proposal could be implemented by a minor change to an existing Act; perhaps by adding something like the words:

“Watchamacallit Bay east of a line from Lottery Point to Cape Kleros”

to an existing list of prohibited fishing zones. This would not alter the process of review, deliberation and voting.

It has been suggested above that “A chamber chosen by lot could also use the “wisdom of the crowd” (for instance to estimate budget allocations: the median of the members’ estimates would serve as the allocation for the following year)” In connection with this, it is worth quoting the Wikipedia article on Francis Galton:

Galton was a keen observer. In 1906, visiting a livestock fair, he stumbled upon an intriguing contest. An ox was on display, and the villagers were invited to guess the animal’s weight after it was slaughtered and dressed. Nearly 800 participated, but not one person hit the exact mark: 1,198 pounds. Galton stated that “the middle most estimate expresses the vox populi, every other estimate being condemned as too low or too high by a majority of the voters”, and calculated this value [in modern terminology, the median] as 1,207 pounds. To his surprise, this was within 0.8% of the weight measured by the judges. Soon afterwards, he acknowledged that the mean of the guesses, at 1,197 pounds, was even more accurate.i

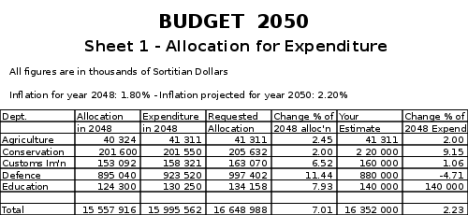

Well before the budget date, the various Departments, Boards, and other administrative bodies would prepare their estimates. A month or so before the budget was due to be discussed, a printed table would be supplied to all members (and made public on the government web site). This table would list, for each body, its requested allocation, the allocation made for it and the money actually spent in the latest year for which figures are available, and a blank space for the member to insert his or her estimate of what the allocation should be for the coming year. Also printed on the same table would be the past inflation rate and estimated inflation for the coming year, and the total budget sum requested by Treasury, and Treasury’s preferred surplus or deficit.

A complementary table would show the revenue raised in preceding years from each source, and the estimated revenue for the coming year if no changes were made to the existing methods of raising income, and of course, a blank space for the member’s proposed figure.

Time would be set aside on the Agenda for the discussion of the various items, and for members to question the Oversight Committees and if necessary the heads of Ministries on their projected needs and past expenditure.

Finally, each member would submit his or her tables with the blanks filled in, and the median value for each allocation and revenue proposal would be calculated.

The following tables are examples only. (The figures in the columns “Your Estimate” represent what a hypothetical member might propose.) Obviously there would be many more items than are shown here.

In practice, both the Members and the clerks of the Assembly charged with calculating the median of each estimate would probably use spreadsheets; the paper tables, however, would be submitted as a vote, and would provide a hard copy that could be used for checking.

For each budget item the median value of the members’ proposed figures would be taken. (The median value is the “middle-most” value if there is an odd number of estimates, and the mean of the two middle-most values if there is an even number of estimates.)

It is important that it should be the median, and not the mean. If all members were sincerely trying to guess a reasonable figure, the mean might give a slightly “better” estimate, as Galton observed in the case of the ox. However, if the mean value is used, an eccentric or extremist member could disproportionately influence the final value by nominating outrageous figures.

For example, suppose that in our example 499 members make an honest attempt to choose a reasonable figure for Conservation and Defence, and that the mean of their proposals is 200 million Sortitian Dollars for Conservation, and 900 million for Defence, and that most estimates are fairly closely clustered around those two figures.

One member, a fanatical pacifist/ecologist might propose the absurd figures of 1 trillion (1 million million) for the Conservation budget, and 0 for every other budget item including Defence. The final mean budgets would be:

Conservation . . . 2 199.6 million

Defence . . . 898.2 million

The effect on Defence is slight (0.2%), but the effect on Conservation is huge, (the budget would be 11 times the mean estimate of the other members), which is clearly against the intentions of the majority of members, and consequently against the aggregate of the wishes of the public.

However, if the median figure is used, the effect of a few unreasonable estimates will be very slight. If, as is likely, the estimates (of the other 499 members) for Conservation nearest to the median are closely grouped, and look something like:

. . . 199.5, 200, 200, 200 (median), 200, 201, 201.5, 202 . . .

(ie several members are very close to, and some actually hit the median) then one absurdly high estimate will have the effect of moving the median one place to the right, in our example from 200 million to . . . 200 million.

Although in most cases the estimates will tend to be clustered about the median, even if they are not it would take quite a weird distribution of estimates for one “outlier” to have a very great effect, since in any case the median cannot move beyond the next highest estimation. Another plausible, though less likely, distribution – much less clustered about the median – might be:

. . . 180, 190, 195, 200 (median), 208, 210, 212, 215 . . .

Even in this case our fanatic would succeed only in moving the median value from 200 to 204 (half-way between 200 and 208), a change of 2%. This is hardly likely to do much damage, and we note incidentally that he could have achieved the same effect with the much more reasonable estimate of 208 million.

Fixing the budget estimates is probably the most important exercise of the legislature, for it fixes the emphasis placed on all aspects of the administration. At present with our elected governments the process is highly political, driven by ideology and interest groups. It is one area where a government chosen by lot could really shine by intelligent apportionment of resources, and by fairness in raising revenue.

Example 3: Abusive use of Proposals by Minorities or Individuals

Suppose a minority group wishes to impose its moral code on the public.

For instance, suppose a group of earnest vegan/animal-rights enthusiasts wishes to abolish all eating of animals, the eating of eggs, all killing of animals for meat, fur, feathers, or whatever; all keeping of animals in captivity, all experiments on animals, and of course all fishing and collection of shellfish.

It makes a proposal to this effect, and after the appropriate steps described in Example 1, the bill is presented to the Assembly, which after debate rejects it by a large majority.

The animal rights group then proposes the same measure again, without amendment, and publicly states that it will do this every day until the bill is passed.

If significant changes had been made to the bill, we might believe that the group was acting in good faith, and that the revised bill should be re-examined, meaning that it should go back to the SIPC, new submissions called for, new debates and recommendations made by the SIPC, and finally, new debate and a vote in the Assembly.

However, in this example, no significant changes have been made, so this is clearly an attempt to impose a minority view on the majority.

What should be done? It would be possible for either the Proposals Committee to refuse to forward it to the Agenda Committee or for the latter to refuse to put the bill on the agenda, for a given period or until an amended version was proposed.

A more democratic solution would be to put it on the agenda for immediate vote in the Assembly, perhaps as the first bill of the next day. Of course it would be rejected again, without delay, as no further discussion would be necessary. If other groups or individuals acted in a similar way, one might imagine dozens – or more – bills being re-proposed frivolously every day. However, this need not be a problem. If all cases were as clearly abusive, the Assembly might vote every morning to reject the whole lot en bloc in a few minutes.

Alternatively, it might pass a measure to the effect that no rejected bill might be re-presented without amendment (not just the form, but the substance) for a given period: three years, for instance. Or it might pass a measure authorising the Proposals Committee to use its judgement to eliminate such proposals.

Whatever the solution chosen, it should be the Assembly that makes the decision.

Example 4: Very Close Votes in the Assembly

It is unlikely that very close votes will happen often. In practice, when the public and the Assembly are nearly equally divided on an issue, it is probable that an amendment or a “third way” would be found that would find favour with a greater majority.

Why is this likely? Because it would be in the interest of everyone to find such an amendment or alternative. Those in favour of the bill would have a greater chance of seeing it passed by removing unpopular elements. Those who were opposed would of course seek a more palatable alternative, and those who had such strong reservations that they were unable to decide, would surely seek to ameliorate a doubtful measure, by removing provisions which they objected to.

How might the Assembly deal with close votes if they do occur? One good way would be for the Assembly to decide that any measure passed or rejected by less than a given majority should be re-considered by the Assembly after a fixed period.

Suppose that an animal welfare group (perhaps after the previous example) puts forward a proposal to limit cruelty to animals in farms, abattoirs, and laboratories, and that this more moderate bill is approved by a majority of eight votes. The Assembly has decided that bills approved by fewer than ten votes will be automatically on the agenda for reconsideration after five years. Now suppose that when the bill comes up again, industry and farmers have learned to live with its provisions, public attitudes have changed so that more people have come to think that animal suffering should be reduced as much as possible, and the bill is passed with a reasonably large majority.

On the other hand, if, in the light of experience, the bill was found to be unsatisfactory, it could be repealed or amended until acceptable to a larger majority.

What about tied votes? The issue could be resolved by the casting vote of the Speaker, if he or she does not normally vote, as happens in elected parliaments. This is not really satisfactory: such close votes mean that about half the population – in some cases more – will be dissatisfied. It would be better for proposals which receive a majority of less than, say, 5 votes to be referred back to the Policy Committee or SIPC with suggestions for amendment, and then re-presented to the Assembly. This is equivalent to the suggestion above, with the “fixed period” reduced to zero.

In the case of bills rejected by a small majority (or indeed any majority), those in favour of them would of course be able to modify them and propose them again.

Example 5: A Proposal Originating in a Policy Committee

Suppose that at present, there is a subsidy for the construction of wind-powered generators, and that electricity generated by solar panels receives a guaranteed price. The (permanent) Policy Committee on Energy, taking into consideration advice from its subcommittees, submissions from experts, and its own continuous reviewing of the scientific and technical literature, decides that it would be better to abandon the construction subsidy and the fixed price altogether, and instead to subsidise all electricity on a sliding scale, based on the environmental costs of new installation, the environmental cost per unit generated, and the degree to which the supply curve of electricity generated matched the demand curve. In this scheme a particularly polluting or inefficient method of generating electricity would then have a “negative subsidy”, that is, it would be taxed.

The Policy Committee submits its proposal to the Proposals Committee, which acknowledges receipt on the government website, notifies the Agenda Committee, and refers it to the parliamentary draftsmen, to be put in proper form. After checking for incompatibility and duplication, the draft is returned to the Energy Policy Committee, and published.

Since the Energy Committee is a standing Policy Committee, there is no need to form an SIPC. The Energy Committee would call for submissions on the proposal as drafted. One might expect in this case a number of opposing submissions from makers of wind-power devices and operators of coal-fired stations, and no doubt some in favour from makers of newer forms of power generation, perhaps also some requesting higher subsidies for an initial period.

The Energy Committee and its various sub-committees would debate all this, and might amend its proposal in the light of the new submissions, in which case the bill would again go to the draftsmen, and back to the Energy Committee before going to the Agenda Committee to be submitted to the Assembly for debate and voting.

At all times the draft would be available to the public, as would the submissions and the recommendations of the Energy Committee and subcommittees.

Sortition and Criteria for Democracy

Let us now consider how the proposed sortition-based government compares with the criteria for democracy given above.

Comparison with the Criteria of Fishkin

Political Equality

If the Assembly is chosen fairly, at random, from the entire adult population, then in effect, the whole adult population participates when the members of the Assembly debate and vote. So “formal political equality” is achieved, at least as far as adults are concerned.

The absence of re-election removes the major source of corruption. The secrecy surrounding each member’s vote, both before and after it is cast, will make it very difficult to either bribe or threaten a member. There will be no way of knowing how many members, and which, to target in order to change a decision, and no way of knowing whether the bribes or threats had any effect. The danger of being denounced would be very high. So we can say that the requirement of “insulation” is met.

The function of the SIPCs is to permit the full range of views to be heard and discussed, to study them, and to present them to the Assembly with the recommendations of the SIPC members. This should provide very “effective hearing”.

Theoretically, at least, political equality is achieved.

But what is the likelihood of de facto inequality arising from undue influence being wielded by experts who have an axe to grind? Moreover, one cannot entirely exclude the possibility of experts who have an entirely erroneous opinion swaying the vote in the Assembly. Expert evidence has after all misled courts and led to miscarriages of justice. The safeguards against error and bias in the expert opinion are:

1. The right of any member of the public, expert or not, to make a submission to the SIPC, and thus to oppose a submission or opinion already expressed.

2. The right, or rather the duty, of members of the SIPC to call for opposing opinions.

3. The right of members of the SIPC, the Assembly, and the Review Chamber to ask for detailed, rational justification of an opinion, or to disregard any opinion they consider unbalanced or unsupported by the facts and logical argument.

It is thus very unlikely that a blatantly biased or erroneous “expert” opinion would go unchallenged by other experts. If the experts disagree, there should be a lively debate, and the Assembly and the public will be able to judge between the arguments advanced to support the opposing opinions.

(Of course, it is possible for the all the experts to agree and for all to be wrong. There is nothing sortition or any other political system can do to fix this; but then this has nothing to do with political equality.)

Non-tyranny

It is impossible under any system to give a cast-iron guarantee that there will never be tyranny.

Since we are not at present discussing tyranny imposed from the outside (for instance, by a foreign power), or despotic or oligarchic regimes, where tyranny is “built-in”, we need only consider two types of tyranny here: tyranny by minorities, and tyranny by majorities.

Tyranny by Minorities

Majority rule, together with random selection from the whole adult population should guarantee that minorities do not tyrannise majorities. However, we should look at the possibilities for failure of the system.

The first possibility is that a lack of formal political equality could permit a minority to get its way unjustly. This possibility has in effect already been considered above in discussing political equality.

We should note a second possibility: suppose a bill is narrowly passed, say by 250 votes to 249, when in fact 50.1% (say) of the population is opposed. This is just possible, since the representation of the population by the Assembly cannot be more than a close approximation.

In Example 4 we noted that such close votes are improbable, and suggested ways of dealing with them. Assume, though, that the bill is passed by this slender majority, and that there is no automatic reconsideration. It is not hard to see that sooner or later, with the regular change in membership, an Assembly would come that opposed the measure by a slight majority and presumably would revoke or amend it. If this did not happen, it would mean that public opinion had changed, and that experience had shown that the measure was satisfactory to the majority.

A third possible form of tyranny is that members of the Assembly might be bribed or coerced. This is much less likely with sortition than with elections.

Since members cannot be re-elected, and no-one can know who will be chosen by lot in the next draw, we have eliminated the possibility of members being promised support – whether money or favourable publicity for their election campaign – and also the possible threat of withdrawal of such support.

The scope for bribing members will be much reduced from the possibilities available under electoral democracy. In the absence of clear political loyalties, it will be less obvious how members are likely to vote on a particular measure at least until they speak, and so less obvious to whom a bribe should be offered, and how many members would have to be bribed. Any member tempted to accept a bribe would know that for the bribery to be likely to succeed it would be necessary to bribe several members. Any one of these could spill the beans, so the risk of accepting a bribe would be high, and so the risk of offering one would also be high. Finally, since voting in the Assembly would be secret, there would be no way of knowing whether a bribe was effective: a corrupt member could simply pocket the bribe, and then cast his vote any way he wished.

Bribing a member to propose a measure would make no sense, since any member of the public could do that, including the person who considers offering the bribe.

Consequently, anyone wishing to influence the vote would almost certainly get more “bang for the buck” – with no risk – by mounting an advertising campaign, by making submissions to the SIPCs or by offering money to disc jockeys or other public figures to express opinions in the sense desired.

This brings us to a fourth possibility, that wealthy interests could influence public opinion, and hence the opinion of the Assembly by dishonest advertising campaigns, biased reporting in the media, and so forth.

The danger of this cannot be denied. It certainly happens at present in “representative democracy”

With sortition, it probably cannot be entirely eliminated. However, it will be mitigated by:

- The process of deliberation in the SIPCs and the Assembly, meaning the ability to express opinions, questions and answers free of the necessity to score political points against opponents, and free of the fear of political embarrassment.

- The freedom of the public, including recognised experts, to make submissions to the SIPCs.

- The fact that each SIPC will have the time and resources to examine its single issue thoroughly and to acquaint itself with the facts. The Assembly, too, although its time will be split over a large number of issues, will still have more time to honestly consider issues than elected politicians whose minds are set on re-election, and whose speeches are aimed at countering their political opponents.

- The public information services, financed by the state, but not beholden to any political party or individual, would present a more balanced coverage of news and opinion than news services run by large corporations.

Tyranny by the Majority

This seems to concern Americans much more than other people, probably because of the use of the expression by John Calhoun, who campaigned vigorously and eloquently in the first half of the 19th century against the “tyranny” of the majority (the northern states) which sought to outlaw slavery, against the wishes of the “oppressed” minority (the southern slave-owners).

In spite of this unsavoury connection, the possibility of tyranny by the majority must be considered. It certainly happens in “representative democracy”: one has only to consider the historical treatment of homosexuals.

The measures proposed or instituted to prevent majority tyranny, such as “super-majorities”, the possibility of appeal to a Court with constitutional powers, or a Senate formed as in the US and Australia, where each state has equal number of votes, only tend to bring about a tyranny by minorities. The reader who doubts this is referred to Robert Dahlii who has examined the question in detail.

Majority tyranny could also happen with sortition. As an extreme example, with no children in the Assembly, in theory there would be nothing to stop the adults deciding (on the principle of “spare the rod, spoil the child”) that every person under 16 should receive a caning every day as a prophylactic measure. Not being present in the Assembly, children could do nothing to prevent this.

The safeguards against majority tyranny are:

- A high level of public education and public information.

- The general sense of fairness of most people.

- The consideration in each citizen’s mind that an injustice done to one minority today could be done to another tomorrow, and that everyone is a member of some minority at some time.

We must conclude that no guarantee can be given against the tyranny of the majority with sortition. Would it be less likely than at present with elected governments? There are some reasons for hope:

- Minorities would be represented in the Assembly, where they can make their views known. They may be completely excluded from an elected parliament.

- All citizens, including members of minorities would be free to make proposals on matters important to them. Even when rejected by the Assembly, such proposals would make the majority aware of the minority’s concerns, and would no doubt attract some sympathy, perhaps leading in time to a proposal that is accepted by the Assembly.

- The perverse effect of the subsidising of campaign costs by the state (which reinforces the larger parties) would be absent. (see §5 above)

- The problem of ignorance (rational or otherwise) when voting on a measure will be greatly reduced if not eliminated in the SIPCs, which will have the time to study their single issues in depth. If a proposal tends to disadvantage a minority, that minority will be able to object, and the SIPC will be able to take the objections into account.

- The need for parties disappears with sortition, so the polarisation of views, the mindless chanting of slogans, the singling-out of scapegoats, and the slurs and denigration that go with elections will be unnecessary.

- Non-partisan state-financed news services would give a more balanced and less superficial treatment of news than commercial media.

- One could expect inequalities in education to be reduced or eliminated in a true democracy.

It is true that the expression “general sense of fairness” may not inspire much confidence in those whose opinions or culture are beyond the pale of tolerance for the majority, such as (today): those who wish to practise ritual cannibalism, incest, or bestiality, or to eat pork or beef in certain countries; or (in former times): atheists, homosexuals, transsexuals, heretics, and those guilty of dancing on Sundays.

On the other hand, daily caning of children for no reason is not common, so presumably some “general sense of fairness” must exist.

Deliberation

In its passage from bright idea in Bill Brown’s head to becoming law, the proposal of Example 1 has been examined by the Proposals Committee, by the professional draftsmen, by the Agenda Committee, by the Single Issue Policy Committee and the experts it called, by any Ministries affected, by anyone who made a submission to the SIPC, by the Agenda Committee again, by the Assembly, and if it exists, by the Review Chamber. If amendments are proposed, it may pass by these bodies several times. It has been debated (in the sense of arguments for and against it being advanced) before the SIPC and in the Assembly and (if there is one) in the Review Chamber.

We may conclude that Fishkin’s requirement of “deliberation” has been fulfilled.

Comparison with the Criteria of Dahl

Effective Participation

If we accept that the bodies chosen by lot, the Assembly and the SIPC, in their composition accurately represent (“stand for”) the adult population, then it is clear that they may represent (“act for”) them in making decisions. Thus when these bodies debate and vote the effect is the same as if the whole population debated and voted. To be sure, the SIPC, having fewer members, will less accurately reflect the public than the Assembly, but it is the Assembly that has the final say, not the SIPC.

It is also possible for the ordinary citizen to make a submission to the SIPC supporting, opposing, or suggesting a modification to any proposal.

Thus this requirement is met.

Voting Equality at the Decisive Stage

The decisive stage for all measures will be the vote in the Assembly. Voting here is strictly equal between members, and the members are free to vote without fear or favour. Again we invoke the principle that a sufficiently large body chosen by lot will in its composition accurately represent (in the sense “stand for”) the adult population, and that it may therefore reasonably act for it in making decisions. Consequently the choices of the citizens, all the choices, and only those choices will be taken into account.

Enlightened Understanding

Since all information will be publicly available, it is possible for anyone to inform himself or herself on any proposal at any time after it is made.

However, since in practice we do not have enough time to investigate every topic, and we cannot all become experts on everything, under any political system we must in effect delegate our right and our duty to inform ourselves, at least on those topics which are of lesser interest to us. This delegation is not “alienation” since we do not give up our right to inform ourselves on any matter.

The delegation is surely best made to someone whose views on the matter in question resemble ours, and the best way to achieve this, for the whole population, is by means of a random sample.

The proposed system satisfies the requirement of enlightened understanding within the limits of what is possible.

Control of the Agenda

Dahl’s expression is “The demos must have the exclusive opportunity to decide how matters are to be placed on the agenda of matters that are to be decided by means of the democratic process.”iii

Since the agenda is proposed by the Agenda Committee, which is not truly representative, it might seem at first glance that this requirement is not fulfilled. However, the Assembly has the final say on agenda matters as on all others, so is quite free to modify the agenda, every day if it sees fit, though this seems highly unlikely.

Certainly, control has been delegated, and more than once: from the population to the Assembly, and from the Assembly to the Agenda committee, and to the SIPC. The second delegation is eminently revocable, as just explained. So, too, is the third. The first (and to a great extent the third) is a delegation to a group whose views are ours, and will act as we would.

Any danger to democracy would come not from placing unpopular or undesirable matters on the agenda (they would quickly be voted down), but from a refusal to put a matter on the agenda which ought reasonably to be there.

While the Agenda Committee might have reservations about, or be prejudiced against a proposal, every citizen has the right not only to make proposals, but also to campaign for them to be considered. Also, the SIPC members could be expected to push for “their” issue to be heard. The Assembly can at any time modify the agenda in order to consider proposal immediately. So it is hard to see how the Agenda Committee could delay a proposal without good reason. In any case, the Agenda Committee is replaced every six months.

The conclusion must be that this criterion is met.

Inclusion

All adult citizens who are able to participate are included in the draw for all bodies chosen by lot. Those chosen must formally refuse if they do not wish to serve.

This condition is met within the limits of what is possible.

Tabular Comparison of Elective Government and Sortition, using the Criteria of Fishkin and Dahl

| Criterion | Elective Government | Sortition |

|---|---|---|

| Fishkin | ||

| Pol. Equality: Formal | Not met | Met |

| Pol. Equality: Insulation | Ineffective | Effective |

| Pol. Equality: Effective hearing | Not met | Met |

| Non-Tyranny | Not met. Tyranny occurs, both by majority and minority | Tyranny by minority very difficult; by majority possible, but less likely than with elections |

| Deliberation | Unsatisfactory both on issues and on candidates | Unlimited except by time |

| Dahl | ||

| Effective Participation | Very limited | Met |

| Voting Equality | Not met | Met |

| Enlightened Understanding | Not Met | Met |

| Control of agenda | Not met | Met |

| Inclusion | Met in the better states | Met |

Campbell,

I forget how many allotted members you allocated to the Proposals Committee, was it ten? The current count for UK Government E-petitions is 59,548 and this is despite the fact that all petitioners stand to gain is the possibility of a parliamentary debate (which will have even less efficacy than a Private Member’s Bill) iff they manage to attract 100,000 online signatures. Given that all Bill Brown has to do is fire off an email or letter, this figure will clearly increase by several orders of magnitude, so these 10 random citizens are going to be pretty busy. The sheer number of individual acts of isegoria in large modern states is the reason why a representative filter has to be applied right from the start, so that the allotted members only have to consider those proposals that have already gained a reasonable measure of public support. The numbers suggested here indicate how it would be extremely cost-effective for lobbyists to bribe members to introduce policies direct to the Assembly. Corruption in allotted assemblies can only be avoided if their role is limited to determining the outcome of a debate via a secret ballot.

Thank you for confirming that the Galton project recorded the guesses of villagers, many of whom (especially those who paid to enter the competition with a hope of winning the prize) would have had some dealing with livestock (or deadstock). Not so in your example (setting a multi-billion pound budget by pure guesswork). As I pointed out earlier, you are conflating the wisdom of crowds and the law of large numbers.

>If we accept that the bodies chosen by lot, the Assembly and the SIPC, in their composition accurately represent (“stand for”) the adult population, then it is clear that they may represent (“act for”) them in making decisions.

I couldn’t agree more. Note that “making decisions” does not require a single speech act — all you do is tick the ballot paper.

>the Assembly has the final say on agenda matters as on all others, so is quite free to modify the agenda, every day if it sees fit, though this seems highly unlikely [my emphasis].

Exactly, as the choices of the assembly will be limited to those presented to it by the oligarchic Agenda Committee, so it’s freedom is severely constrained. This is a clear breach of Dahl’s requirement that the demos must have the exclusive opportunity to decide how matters are to be placed on the agenda. At least our current arrangements allow all voters to choose between competing oligarchies (polyarchies, in Dahl’s terminology), whereas the poor sots in your Assembly are restricted to what is served up to them by a purely aleatory process (in the disparaging sense of the word).

I’ll leave the final word on your project so far to John McEnroe: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ekQ_Ja02gTY

LikeLike

Campbell,

More good stuff here. Many of the details I would favor amending, but ultimately experience would tell. Indeed, in many respects this mirrors my own multi-body sortition model. I strongly agree that it is important that different bodies of people have responsibility for different tasks along the way of law-making, both to allow focused attention, but also as a check on one another.

One element I think is intriguing but probably should be left out of the final version of this essay is the median setting of budgets. There could well be times when this would work well, but others when it would fall down badly. I am not concerned about their lack of knowledge, which Keith raises, since they are basing their picks on expert-prepared proposals. My concern is for budget options that do not have a neat linearity. For example, a department’s base budget might be 70 million dollars, and they could incorporate the additional project X in the annual budget for an additional 10 million. If some Assembly members favor X and some don’t the median might be 64 million…not enough to do a decent job with project X, but a wasteful excess if project X is abandoned. In other words, some budgets are inevitably formed with steps, rather than a smooth gradation. Yes, there might be some way to deal with this, within your median scheme, but since it really is NOT inherent in a sortition proposal (an elected legislature could decide to use this median budget setting system if they wished), I would suggest deleting it as a distraction.

LikeLike

@ Keith

>”I forget how many allotted members you allocated to the Proposals Committee, was it ten? The current count for UK Government E-petitions is 59,548 and this is despite the fact that all petitioners stand to gain is the possibility of a parliamentary debate (which will have even less efficacy than a Private Member’s Bill) iff they manage to attract 100,000 online signatures. Given that all Bill Brown has to do is fire off an email or letter, this figure will clearly increase by several orders of magnitude, so these 10 random citizens are going to be pretty busy.”

Not a problem. If we need more members, or a number of sub-committees, the mechanism is there for the Assembly to make the necessary adjustments.

>”The numbers suggested here indicate how it would be extremely cost-effective for lobbyists to bribe members to introduce policies direct to the Assembly.”

I don’t know why you think it is possible for a member to introduce a policy directly. A member of the Assembly, being a citizen, can propose a measure, and it will pass through the same process as Bill Brown’s.

A lobbyist can also do this. So to bribe a member to make a proposal would be utterly pointless.

>”Corruption in allotted assemblies can only be avoided if their role is limited to determining the outcome of a debate via a secret ballot.”

A secret ballot is an essential part of this proposal.

>” the Galton project recorded the guesses of villagers, many of whom (especially those who paid to enter the competition with a hope of winning the prize) would have had some dealing with livestock (or deadstock). Not so in your example (setting a multi-billion pound budget by pure guesswork)”

Using the words “pure guesswork” here is (pure) nonsense.

In fact, the members will have quite a lot of information available. They will know the more important economic figures, eg revenue and expenditure and surplus/deficit for preceding years, public debt, inflation, unemployment etc, and the views of Policy Committees on economic topics.

For each budget expenditure item they will have:

1 The estimate from last year.

2 The estimate for the current year (I omitted this in the table, but clearly it will be available)

3 The amount actually spent last year.

4 The estimate if they adopt a “steady as she goes” approach (actual expenditure corrected for inflation)

5 The allocation requested by the department or board in question.

6 The department’s justification of this request, including a break-down of all projected expenses.

7 The views of the Oversight Committee members (This is an omission in the text, I shall fix it)

8 The views of any relevant Policy Committees.

9 Their own priorities. The member used as an example clearly wants to spend more on conservation and education, and less on defence.

(Yes, for reasons of space items 2 and 4 don’t appear in the table.)

For revenue, they have for each item:

1 Last year’s estimated revenue.

2 Last year’s actual revenue.

3 The current year’s estimate.

4 The “steady as she goes” figure calculated from estimated inflation.

5 The views of relevant Policy Committees.

5 Their own opinion of a fair way to share the costs. The member used as an example thinks property owners should pay more, and that alcohol should be taxed quite severely.

If five-year terms are used, four-fifths of the Assembly will have already been through the exercise, and seen the results of their choices, so all of that information is available to them. Even if three year terms are used, there is a majority of experienced members. So the estimate that each member reaches will be an informed estimate. You might argue that there is too much information available. However, there is a “safe” option for those who feel they don’t completely understand the ins and outs of a particular item; that is, of course, the “steady as she goes” estimate. And using the median means that a few wild estimates will not have much effect.

>”the choices of the assembly will be limited to those presented to it by the oligarchic Agenda Committee, so it’s freedom is severely constrained. This is a clear breach of Dahl’s requirement”

This is simply false, Keith. The Assembly has the final say. What could be more clear?

>>” it is clear that they may represent (“act for”) them in making decisions.”

>”I couldn’t agree more.”

I’m a little surprised, I thought it was here that you had discovered my lunacy. I come to speeches later.

@Terry

>” Indeed, in many respects this mirrors my own multi-body sortition model”

That is no accident, Terry. I have been much influenced by your ideas, and by those of Alex Guerrero and John Burnheim, and I’m grateful to you.

>” I think is intriguing but probably should be left out of the final version of this essay is the median setting of budgets. . . My concern is for budget options that do not have a neat linearity. For example, a department’s base budget might be 70 million dollars, and they could incorporate the additional project X in the annual budget for an additional 10 million. If some Assembly members favor X and some don’t the median might be 64 million…not enough to do a decent job with project X, but a wasteful excess if project X is abandoned. In other words, some budgets are inevitably formed with steps, rather than a smooth gradation.”

Terry, I think the danger of one fanatic throwing a spanner in the works is too great to be ignored if the mean were used. If I say nothing, it’s an easy target for a malicious critic (there just may be some out there, somewhere).

I take your point about stepwise budgets, but if project X is marginal, in the sense that all other projects and expenses are either more important or cannot be avoided, then it seems (to me) best to shelve project X, and if all the projected numbers turn out to be right, there will be 4 million left over. Would that be a catastrophe?

More likely, though, the estimates will be a bit out (I would guess most often too low), so that even if the allocation exactly matched the requested one, there would be some project left short of money. If it’s project X, and the Assembly has legislated that project X must go through, then project X is not marginal, reality will strike, and there will be a blow-out of the budget – just as happens now.

I’ll reply to your comment on the length of terms of service on the other page.

LikeLike

Campbell,

>A member of the Assembly, being a citizen, can propose a measure, and it will pass through the same process as Bill Brown’s. A lobbyist can also do this. So to bribe a member to make a proposal would be utterly pointless.

Because as a fellow oligarch, the committee is likely to privilege her proposal over the 100,000+ coming from the likes of Bill Brown. Or do you propose introducing a double-blind review process?

>A secret ballot is an essential part of [my] proposal.

Yes but, from an anti-corruption perspective, it should be the only role of allotted members. Open it up to speech acts and corruption is highly probable, if not inevitable.

Hopefully Terry’s wise counsel will prompt you to drop your proposal for budget setting by median guesswork, so I don’t need to labour that point.

>This is simply false, Keith. The Assembly has the final say. What could be more clear?

Dahl’s requirement (your citation) is that the demos must have the exclusive opportunity to decide how matters are to be placed on the agenda. This is denied to them by your oligarchic vetting committees.

>>” it is clear that [allotted members] may represent (“act for”) [all citizens] in making decisions.”

I’ve consistently argued that a statistically-representative sample of all citizens is the democratic forum for making decisions (voting), so why would I find such a proposal “lunatic”?

LikeLike

Hi Campbell,

In my mind the problem with the agenda setting process you are proposing is that it is yet another mass–political arrangement. That, it is a situation in which very many people are nominally on an equal footing. Each citizen is nominally able to make proposals and to “do his homework” and thus get his proposal considered by the representative committee.

In reality, however, any such process would tend to become dominated by an organized elite. A set of people and institutions with resources and experience would be in a much better situation to navigate through the process – hiring professionals to write up supporting opinions, collecting signatures for petitions, and overcoming any other hurdles.

In practice, there would be a stratification of proposals, where the proposal of the average person gets lost in a mountain of other proposals, while the proposals that are backed by elite powers get a good chance of becoming part of the agenda.

Here, as always, the dynamics of “mass politics” have to be kept clearly in mind when attempting to design a system that is really democratic rather than merely nominally “equal”.

LikeLike

Agree with Yoram’s observations on the stratification of proposals (the only exception being the pet projects of the aleatocratic oligarchs). How to establish isegoria in extended and densely-populated states is a non-trivial problem.

LikeLike

Just in case this isn’t clear – it is exactly the proposals of the allotted that should be getting the preferred treatment. Those proposals are representative of the population. What I find prolebmatic is that the allotted would not be able to promote their agenda due to the constraints of the proposed mass-political process.

LikeLike

Yoram,

Thanks for confirming your preference for aleatocratic oligarchy, in which the vast bulk of citizens lose their right of isegoria, viewed by most scholars to be the quintessence of the Athenian democracy. Both Campbell and Terry at least attempt to retain this right, even though their proposals are flawed as they replace a democratic filter with an oligarchic one.

LikeLike

Keith, (I forgot to post this) Wrt:

>”The current count for UK Government E-petitions is 59,548 and this is despite the fact that all petitioners stand to gain is the possibility of a parliamentary debate”

I’m not a UK citizen, so correct me if I’m wrong, but I would guess the obvious reason is that they are email petitions. Petitioners may have little to gain (you’ve left out kudos amongst the peer group), but it costs them nothing, so there’s no disincentive to frivolous petitions.

This is a minor practical problem. (The Assembly might require that proposals should be in letter form – they can be scanned – and include a stamped, self-addressed envelope. Ah, nostalgia! They could be really nasty, and require a hand-written copy as well as a printed one to discourage the schoolkids!) If the public is aware that something a bit more serious than Bill Brown’s effort is required, there will probably be a lot fewer proposals. If the Assembly considered that there were too many frivolous proposals, I suppose it could set a small fee; I wouldn’t like to see a high one.

Still, you’re almost certainly right in thinking that one Proposals Committee is too little for a country the size of the UK, though in Nauru or Antigua they could probably spend every second day fishing (if fishing is still permitted). I think I’ll change my text to spell out that there will be sub-committees as required.

@Yoram and Keith

>”In practice, there would be a stratification of proposals, where the proposal of the average person gets lost in a mountain of other proposals, while the proposals that are backed by elite powers get a good chance of becoming part of the agenda.”

No doubt there would be a stratification of proposals, though not necessarily along the lines that you and Keith suggest.

I would expect that the Proposals Committee would favour proposals which are

1 clearly expressed,

2 set out precisely what the intended effects are of the new measures proposed,

3 produce evidence to justify the intent of these measures,

4 produce evidence that the measures will produce these effects and no other undesirable ones,

5 produce evidence that the measures are supported by a significant number of people.

(This is a minimum. Maybe the Proposals Committee would find other criteria after some years experience.) The question is really “Can this bill be voted on in the Assembly after minimal changes to wording by the draftsmen? If so, speed it on its way, if not send it back with a note saying why.”

Bill Brown’s proposal meets none of these criteria, and in addition has a glaring logical blunder: if there really are *no* fish in Watchamacallit Bay, then forbidding fishing there won’t make a scrap of difference.

I would expect any proposal that was as badly-presented as Bill Brown’s to be sent back for more info, as happens in the example.

Now certainly meeting those five criteria would mean work, some intelligence, and often specialised knowledge.

And clearly it will be easier for groups such as Policy Committees which have been studying a field for years, or an industry group with large resources to produce polished proposals that meet at least the first four of those criteria.

But does democracy require that vague, ambiguous, illogical proposals with no evidence of their desirability, feasibility, and popular support be treated equally with clear proposals with good supporting evidence? Surely not. That would be like claiming that creationism and evolution should be treated equally.

All is not lost for Bill, of course. If Watchamacallit Bay really is over-fished, and not a poisoned desert, and if a simple ban on fishing will allow stocks to recover, there are probably lots of people who would eagerly get to work and help him, if they are not already out there preparing their own proposal. And he may be able to do some research himself.

>”it is exactly the proposals of the allotted that should be getting the preferred treatment.”

>”as a fellow oligarch, the committee is likely to privilege her proposal over the 100,000+ coming from the likes of Bill Brown”

I disagree with both of you. I worked in the public service for a couple of years in a service that received proposals both from specialists and the general public. Trying to evaluate incomplete and poorly presented ones takes a lot more time and irritates staff, so they get sent back until they are presented in a comprehensible form. I think this will happen with the Proposals Committee, and that strikes me as reasonable.

Keith, “aleatocratic oligarchy” is a mere cheap sneer, and doesn’t help your case. All bodies in my proposal are subject to rotation.

LikeLike

Campbell,

I agree that well-constructed proposals (that privilege the educated middle classes and well-resourced lobby groups) will be more successful than poor old Bill Brown. But you are consistently ignoring the elephant in the room — the huge volume of proposals, once you’ve removed the existing democratic filters. Having said that, the torrent will dry into a trickle once people realise that the chance of their proposal getting a hearing are on a par with the one in a million chance of winning the jackpot in the National Lottery and that the process is just as random. The only exception will be the pet projects of fellow oligarchs.

>“aleatocratic oligarchy” is a mere cheap sneer.

Not at all. The fact that the oligarchs choose to rotate jobs does nothing to achieve Aristotle’s injunction that all should rule and be ruled in turn. This is impossible in large modern states, hence my description of active political functions (other than voting) as oligarchic.

LikeLike

Campbell,

> Trying to evaluate incomplete and poorly presented ones takes a lot more time and irritates staff, so they get sent back until they are presented in a comprehensible form. I think this will happen with the Proposals Committee, and that strikes me as reasonable.

It is indeed reasonable, which is why the arrangement you are proposing is only nominally equalitarian. It is in fact anti-democratic.

LikeLike

Keith,

Your invention and use of the term “aleatocratic oligarchy” is not informative nor helpful for discussion. Oligarchy is generally understood to be based in some sort of class/power/wealth/heredity which perseveres over time… not a jury that is fairly chosen, serves briefly and cannot extend their time, nor select their replacements. Here is what the Merriam Webster concise encyclopedia says about the term:

“Rule by the few, often seen as having self-serving ends. Aristotle used the term pejoratively for unjust rule by bad men, contrasting oligarchy with rule by an aristocracy. Most classic oligarchies have resulted when governing elites were recruited exclusively from a ruling class, which tends to exercise power in its own interest. The term is considered outmoded today because “few” conveys no information about the nature of the ruling group.”

This is absolutely NOT what an allotted system of government would be.

LikeLike

> oligarchic

An oligarchy is a group which holds power on a permanent basis.

As always Sutherland is able to fail to understand any term or statement no matter how clear or simple.

LikeLike

Terry,

Oligarchy simply means “the rule of the few” or “a small group of people having control of a country or organization”. All the other factors (permanence, self-serving, ruling class, bad men etc) are entirely contingent, although I note with interest your implication that random selection from the ranks of the many will be less likely to introduce any of the malign factors (bad men, self-serving etc) than selection from an (aristocratic) pool of the rich ‘n powerful.

>Oligarchy is … not a jury that is fairly chosen, serves briefly and cannot extend their time, nor select their replacements.

Absolutely, that’s why I propose sortition for the selection of political juries. My objection is to Campbell’s (oligarchic) proposal to use sortition to select officials who serve an active political function. This has nothing to do with juries as we normally understand the term. Although the term “aleatocratic oligarchy” does have some added rhetorical purchase, I stand by it as an accurate description of this aspect of Campbell’s project, due to his failure to adequately distinguish between standing for and acting for — a distinction which you (unlike Yoram) have hitherto accepted.

Yoram,

>An oligarchy is a group which holds power on a permanent basis.

What is the provenance of this definition? It’s clearly false etymologically and also untrue historically. Both of the Athenian oligarchies lasted for less than a year. Note that it would also apply to a democracy, where the demos could be said to rule on a permanent basis (although there would be rotation among its representative proxies, whether elected or allotted). In your proposal would it be the allotted group that rules (albeit on a temporary basis)? If so that would clearly not live up to Aristotle’s definition of democracy as (everyone) ruling and being ruled in turn. In my proposal for rule by allotted jury the demos rules permanently as it would not make any difference who was in the group — the outcome would be the same. So is the permanent rule of the demos a variant of oligarchy? I do think we need to be a little more precise in our terminology.

LikeLike

>>An oligarchy is a group which holds power on a permanent basis.

> What is the provenance of this definition?

This is not only standard usage but logically necessary. If any rule by a small group would be considered an oligarchy then any government would be an oligarchy and the term would lose its distinct meaning.

LikeLike

Yoram,

> If any rule by a small group would be considered an oligarchy then any government would be an oligarchy.

The only exception being when the group acts as a direct proxy for the demos. This is an exacting requirement that imposes severe constraints on the operational mandate of the group, but it can be demonstrated to be true or false in practice (by testing if different concurrent samples of the demos return near-identical decisions). Political science is an empirical discipline, not a branch of deductive logic.

LikeLike

> Political science is an empirical discipline, not a branch of deductive logic.

Yes – we certainly don’t want trivialities like logical contradictions stand in the way of scientific progress.

LikeLike

from http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_fallacies

Etymological fallacy – which reasons that the original or historical meaning of a word or phrase is necessarily similar to its actual present-day usage.[31]

Of course the meanings of words change. As an aside, one could make a case that the meaning of isonomia changed between the late 6th century poem attributed to Callimachus. C Trypanis translates “isonomous [adjective] t’Athenas epoiesatan” as “made Athens a city of just laws”, which is not at all the meaning given by Hansen (equality of rights) or Liddell and Scott. Trypanis is/was Professor of Classics at Chicago, so he has some weight. Bailly gives “répartition égale”, equality of distribution, which is closer to the verb nemo “I distribute” from which it derives.

This sort of thing, together with the disagreements between historians about what actually went on in Athens, is another argument to leave Athens out of the equation. Appealing to it as an authority, in the way the scholastics backed up their arguments by referring to Augustine or Origen or whoever, seems futile to me.

If you want me to look up oligarchy, there will be a small fee.

LikeLike

Keith,

In response to Yoram’s objection that your meaning of “oligarchy” would encompass ALL governments (since only a few people are intimately involved at any one time), you wrote “The only exception being when the group acts as a direct proxy for the demos” which you seem to mean a body that does not debate and so statistically it would make no difference who was included…in other words Every government that ever has or will exist is an oligarchy EXCEPT the one specific variant designed by you. Nobody but you uses the word “oligarchy” that way.

LikeLike

Campbell,

Good point. I agree that etymology doesn’t contribute anything to the understanding of how words change their meaning over time. I’ve just completed the first draft of the isonomia chapter in my thesis and argue that a semantic (meaning-in-context) approach is more helpful. But oligarchy, unlike isonomia, is an uncontested concept, as it has always meant the same thing (the rule of the few). The factors that Terry mentioned are entirely contingent and Yoram’s claim that oligarchies are permanent is just plain wrong (they usually only last for a short period of time).

> . . . leave Athens out of the equation. Appealing to it as an authority, in the way the scholastics backed up their arguments

The fourth-century Athenian nomothetai is the only working example we have of legislation by allotted jury, hence the fact that many modern sortition advocates use this as a template for their own proposals. At least we know this system worked tolerably well — that’s why I’d rather base my model on this, rather than resort to deductive syllogisms (Yoram’s preference) or armchair thought experiments.

LikeLike

Terry,

>Every government that ever has or will exist is an oligarchy EXCEPT the one specific variant designed by you. Nobody but you uses the word “oligarchy” that way.

Fourth-century Athenian practice (from which my model is derived) was clearly not oligarchical. Most people would claim the same about fifth-century direct democracy, but I’m sympathetic to the arguments of Yoram and yourself that it was oligarchic in the sense that the assembly was a puppet of the demagogues. As for modern electoral democracy, this is plainly oligarchic when viewed from a synchronic perspective (Lord Hailsham agreed with Rousseau that the English constitution was an “elective dictatorship”), but viewed diachronically it is a polyarchy (of rotating elites). It’s only possible to view electoral democracy as oligarchical when viewed over time if you agree with Marx that all the party leaders are covert members of a single committee for managing the common affairs of the whole bourgeoisie (this appears to be the view of Gilens et al.). I’m inclined to agree with Schumpeter and Dahl that electoral democracy would be better described as a polyarchic rotation of elites. Monarchy is clearly oligarchical as no single person can rule alone, so yes, I do claim that anything other than 4th-century style governance is oligarchic, at least from a synchronic perspective. Note that allotted assemblies start to act in an oligarchic manner as soon as they move beyond an aggregate judgment role, that’s why I view the proposals of Campbell and yourself as democratically illegitimate.

How does this analysis fit with your own understanding of oligarchy (the rule of the few)?

LikeLike

[…] Part 1 Part 2 Part 3 […]

LikeLike

[…] Part 1 Part 3 […]

LikeLike

[…] Part 2 Part 3 […]

LikeLike

Yoram,

>”It is indeed reasonable, which is why the arrangement you are proposing is only nominally equalitarian. It is in fact anti-democratic.”

I think you’re a bit harsh with “anti-democratic”.

It would be a waste of the Assembly’s time to vote on proposals which do not meet the criteria above.

As it stands Bill’s proposal is so vague members would interpret it differently, so a vote would be meaningless.

Some minimum standard must be reached, as with driving a car.

It’s certainly true that some people will be at a disadvantage compared with others. A group of biology/zoology/ecology PhDs would do a much better job of it than Bill has so far. But Bill is not the worst off. It would probably be harder for a group of Amazon Indians who speak little or no Portuguese to defend their forest, but even they could get help from anthropologists, ecologists and the rest. Harder again for the Nicobar islanders; last I heard they negotiated with arrows and spears. Hardest of all for people with locked-in syndrome and a worthwhile proposal in their heads. I can’t fix that.

Don’t forget that only proposals which have significant support will ever get approved in the final vote of the Assembly. Such proposals by definition will have a large group in the community in support, many of whom will have abilities and resources that Bill hasn’t. There’s any number of inexpensive ways Bill could start the ball rolling, maybe even talking to people at his local pub would do.

LikeLike

Campbell,

> It’s certainly true that some people will be at a disadvantage compared with others.

I am not concerned about the natural variation between people. I am concerned about the inevitable gap between the large majority of the population and an organized elite which controls an apparatus that both can recruit professionals to buttress its proposals and can afford signature gathering operations.

> Don’t forget that only proposals which have significant support will ever get approved in the final vote of the Assembly.

If we trust the members of the Assembly to do the heavy democratic lifting, then, why don’t we trust them to do set the agenda as well? Why must they be dependent on an anti-democratic process – which has a built in advantage for the elite – to set the agenda for them?

LikeLike

Yoram,

>If we trust the members of the Assembly to do the heavy democratic lifting, then, why don’t we trust them to do set the agenda as well?

We don’t place our trust in the individual members, we place it in the aggregate vote of the whole assembly, as this is the only level at which the laws of statistical representativity apply. Setting the agenda is the province of individual speech acts and there are no mathematical theorems available to demonstrate the statistical representativity of individual speech acts. This is why your proposal is anti-democratic.

>a built in advantage for the elite – to set the agenda

That would be true if there was a single homogeneous elite. Not so, as modern “democratic” societies are better described as competitive polyarchies.

LikeLike

I think I fit somewhere between Campbell and Yoram on this point. Most average people will be vastly out-gunned in the realm of making proposals in a system where those who are already best prepared and funded can produce ready-to-go proposals. Yoram prefers to let the random assembly members with professional staff generate their own proposals (like traditional elected legislators).

I prefer the idea of an ACTIVE Agenda Council (large and representative – chosen by lot) that will create an agenda for the random assembly and issue requests for proposals to accomplish certain tasks, that the Agenda Council has concluded need addressing (after wide-ranging consultation with experts, interest groups, opinion polls, professional staff, etc.), rather than relying on what proposals happen to float to the top as ready-for-consideration (mostly from well-funded special interest sources).

With Campbell’s design the Agenda Committee is essentially a readiness determining body, in which representativeness is less critical. They are sort of fulfilling a mere ministerial function. While my Agenda Council is establishing a direction for government consideration, though not any details, and not making any final decisions on laws. thus this Council. But unlike Yoram, I agree with those who think the agenda setting process, and the proposal development process should each be carried out by bodies distinct from the process of evaluating (passing) laws.

LikeLike

Terry,

> But unlike Yoram, I agree with those who think the agenda setting process, and the proposal development process should each be carried out by bodies distinct from the process of evaluating (passing) laws.

The question of whether there should be a single body or multiple bodies is secondary and I don’t have a strong opinion on this matter – there are valid arguments both ways.

What is crucial is that any agenda setting body, like any other body with political power, is representative – i.e., in particular, is allotted from the entire population.

LikeLike

>”If we trust the members of the Assembly to do the heavy democratic lifting, then, why don’t we trust them to do set the agenda as well? Why must they be dependent on an anti-democratic process – which has a built in advantage for the elite – to set the agenda for them?”

>”With Campbell’s design the Agenda Committee is essentially a readiness determining body, in which representativeness is less critical. They are sort of fulfilling a mere ministerial function.”

I’m afraid I’m going to dig in here and defend my position.

I think we may be arguing over semantic differences . Terry is quite right, there is a big difference between his Agenda Council and my Agenda Committee. In fact, since they (my AC) have no real authority, it’s a function that could probably be performed by civil servants.

In effect, in my proposal it is the entire citizen body that sets the agenda, in the sense of nominating matters of concern. Surely nothing could be more democratic than that: on the agenda side, we’re in direct democracy.

>”What is crucial is that any agenda setting body, like any other body with political power, is representative – i.e., in particular, is allotted from the entire population.”

I’ve gone one better, the agenda setting body IS the entire population.

As I pointed out, though, proposals for law must meet a certain standard, otherwise they are ambiguous and cannot reasonably be voted on. It is the function of the Proposals Committee (not the Agenda Committee) to refer unclear, nebulous proposals back to their authors for clarification. This is *not* outright rejection.

Whether Bill Brown is just another battler, or whether he has 50 billion in the bank, a dozen PhDs, and a thousand secretaries with legal training, if he is the only one in favour of his proposal, it won’t be passed. If it is a measure that will finally be passed (when all the evidence is produced and the arguments are advanced, dissected, and chewed over), then before that stage it will already have a large body of citizens in favour of it. Amongst those citizens will be people capable of putting it into reasonable form – at no cost to Bill – they are already on board. So although it might take a little longer, if Bill’s bright idea really is a good one, it will go through.

LikeLike

>In effect, in my proposal it is the entire citizen body that sets the agenda, in the sense of nominating matters of concern. Surely nothing could be more democratic than that: on the agenda side, we’re in direct democracy.

The one thing that Yoram and myself agree on (albeit for entirely different reasons) is that direct democracy does not work in large and populous states. When are you going to acknowledge that the inevitably vast number of submissions creates a problem where somebody has to narrow it down to a manageable number and that this should be a truly democratic process? Judging by your vision of patient backwards and forwards exchange between the Proposals Committee and Bill Brown you’ve never been in the role of editor of a scholarly journal or magazine having to manage unsolicited article submissions.

LikeLike

Campbell,

You wrote:

>”In effect, in my proposal it is the entire citizen body that sets the agenda, in the sense of nominating matters of concern. Surely nothing could be more democratic than that: on the agenda side, we’re in direct democracy.”

I (and I’m sure Yoram) disagree. When agenda setting is left to the “entire citizen body” it is elites who define what issues will be taken up through media and other means. Agenda setting is a FUNDAMENTAL POLICY matter. A society shouldn’t focus on those issues that get to the head of the line through appeals to rationally ignorant population as a whole. A smaller (ideally random) group of citizens need to weight the relative priority of issues, because the can’t ALL be taken up in a timely manner.

Agenda setting is a POLITICAL decision-making process, not merely logistical.

It is obvious why special interests with lots of money at stake will have proposals ready to go. But it is harder to say why certain issues that don’t appear to be based in a special interest make to to the top of the public awareness (and thus would generate plenty of thoughtful proposals). Partisans in elections ride both of these agenda setting horses. 1.they generate proposals that will satisfy their supporters (often wealthy, but also merely focused special interests with numbers rather than wealth), and 2. they generate issues for the agenda that they want to campaign on (rather than worry about passing).

Agenda setting is not rational (from society’s perspective) in an electoral system, We need a democratic (descriptively representative) body to decide what issues will be tackled in the current time frame, not only what the specific statute language will say.

As an interesting anecdote on agenda setting…In the 1830’s in the U.S. there was a lot of suspicion of secret societies, the Free Masons in particular, as being dangerous to democracy and freedom. A political party formed around this agenda item…called the Anti-Masonic Party. Few people know about it today, but in my own state of Vermont, the Anti-Masonic Party, riding a wave of conspiracy theories elected the governor and a majority of the legislature, and even gave the state’s electoral college votes to the Anti-Masonic Party candidate for President. The party lasted only a few years, and that agenda item has never resurfaced.

LikeLike

Terry,

>When agenda setting is left to the “entire citizen body” it is elites who define what issues will be taken up through media and other means.