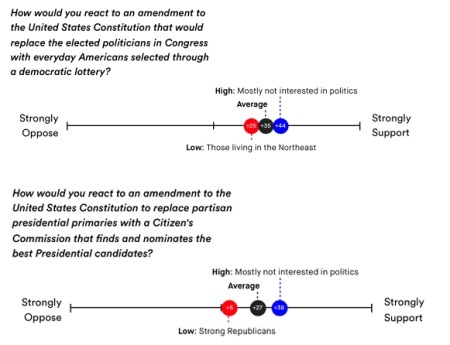

The chart below is excerpted from the results of an opinion survey conducted for “of by for” – an organization working “to get past parties and politicians and put everyday people front and center”. The organization has high profile sortition advocates such as Lawrence Lessig, James Fishkin and Jane Mansbridge as advisors.

Filed under: Elections, Opinion polling, Proposals, Sortition |

On a quick look, that survey doesn’t look like a very solid piece of work

Very dominated by PR ‘messaging’.

LikeLiked by 1 person

But I like the name of the organisation as it weighs equally all three prepositions in the Gettysburg Address.

Yoram:> The organization has high profile sortition advocates such as Lawrence Lessig, James Fishkin and Jane Mansbridge as advisors.

That sounds good to me, but aren’t these the self-same elite of political scientists that you generally disparage?

LikeLiked by 1 person

Nicholas,

The survey was intended to test various framing options. They were testing hypotheses of optimal ways to sell sortition. That is why they talk about a congress of ordinary people rather than politicians, with no focus on the words “sortition,” or “random selection,” etc. The idea is that you sell the CAKE not the RECIPE.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Exact terminology aside (why would anybody use an unfamiliar word such as “sortition” in an opinion survey?), I think the questions about support for constitutional amendments are very interesting. It turns out people are not as protective of electoralism as some think or would have us think.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Expanding on Nicholas’s point, as I see it worse than just PR: The phrasing of traditional questionnaire questions can easily manipulate people, e.g. their first question: After all, who likes “political games”?

The “Congress full of Random Citizens” narrative is naive and misleading. Any sortition democracy needs a much more elaborate institutionalised methodology, not to mention some serious technology.

PS: Americans’ different understanding of the word ‘democratic’ bodes badly for our recent definition exercise.

LikeLike

I disagree (of course?). I think the way people answer certain questions is indicative of their attitudes. The fact that they are ready to consider the radical change of replacing elections with sortition is informative (and encouraging).

I also don’t think that there is any indication, neither in this poll nor any any other that there is wide variation in the understanding of democracy. When it comes to scholars, the situation is indeed very different of course. It is after all, the traditional role of intellectuals to come up with convoluted justifications for the status quo.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Hubertus:> The phrasing of traditional questionnaire questions can easily manipulate people, e.g.:

Indeed, if that isn’t a leading question, I don’t know what it is (an extension of a John Lennon lyric?). No respectable polling organisation (who didn’t have an axe to grind) would use language like that.

LikeLike

*** These polls seem to indicate favorable attitudes of the American citizens towards popular sovereignty through political lot, in all social strata, but with lesser approval in the higher strata.

*** I don’t know of recent French polls about sortition. But, in a book by Luc Rouban (La matière noire de la démocratie) there were data about polls related to the use of referenda. If I remember well (I am confined without the book) the data were, likewise, good feeling towards referenda by all social strata, but with lesser approval or more restricted approval in the higher strata.

*** That seems to indicate a loss of faith for the electoral-representative idea. And that this loss of faith is lesser in the lower strata may indicate that the elitist side of the electoral-representative model is pervading the political culture of the citizenry.

*** But these attitudes are attitudes, not true choices. The lesser approval in higher strata may, at the moment of a true choice, crystallize into a strong hostility against the minipopulus model, fed by united polyarchic forces and grounded on elitist feeling. Would the pro-dêmokratia part of the higher strata be able to resist and stick to the minipopulus idea ?

LikeLiked by 1 person

The polls were about the legislative branch (the Congress) and the executive branch (the presidential primaries). But nothing about the judicial branch. It is strange. It would be logical to poll about an allotted Supreme Court, or, at least, about Simon Threlkeld’ s idea, a constitutional jury which, when there is divide inside the Supreme Court. , would “decide between the minority and majority opinions of the Supremes”.

LikeLiked by 2 people

The stronger support for an aristocratic (presumed to be the best and brightest) legislature among those with more education, may reflect a preference for “expert” technocracy, more than elections themselves — The idea that if reformed and tweaked just right elections could put good competent political experts in power (rather than self-interested elites). When describing sortition to well-educated listeners I find it useful to point out that elected politicians are more interested in listening to their public relations and election strategy experts than policy experts. They also often come into office with their minds made up on many issues and so are psychologically unable to deliberate or absorb contradictory information. I argue that a jury of ordinary people would be far more open-minded, not having pre-judged most issues, and thus would also be far more interested in hearing from policy experts — policy experts who disagree with each other. Facing no re-election, they would have no interest in wasting their time fund-raising or talking with election strategy experts, and so could devote substantially more time and effort on policy. My conclusion is that if you want to bring expertise into governance, you share the interest that ordinary citizens on a jury would also have… consult the best and brightest. This is something elected politicians are not and are not interested in doing.

LikeLiked by 2 people

> if you want to bring expertise into governance, you share the interest that ordinary citizens on a jury would also have

Makes a lot of sense to me, but elitists often have the implicit idea that people are too stupid to be able to evaluate expert opinion, and possibly too stupid to even seek it.

LikeLiked by 1 person

***The very good discourse developed by Terry Bouricius is actually a strong apology of democracy-through-minipopulus as the more « rationalist » of the political models.

*** Against it there is the hard elitist feeling as underlined by Yoram Gat.

*** But more maybe. I know some « scientist » circles in France, defending « rationalism » against the « pseudo-sciences » and what they feel « anti-science » (anti-vaccine, homeopathy, astrology – and actually many sides of the Green movement). Clearly they don’t like much the idea of mini-populus. I think I can give their response to Bouricius’ discourse : « You are right, the polyarchic political elite is not the ruling elite we dream about. But at least these politicians are wily people, not easily tricked, whereas the citizen juries will be easily outmanoeuvred by militants supporting pseudo-science and anti-science, often members of the educated strata ».

*** Their distrust comes specially from some « deliberative democracy » experiments where experts, militants and allotted citizens are blend and discuss face-to-face. They consider the militants will win easily.

*** Acceptation by US judicial juries of what they consider « pseudo-science » as the « repressed memory » or dubious science about some technological risks are arguments against juries.

*** Maybe their political ideal would be an aristocracy of scientifically educated citizens listening to the Scientific Establishment (Academies of Science etc). But I am afraid the polyarchy will be their second best.

*** To convert to dêmokratia these « scientists », or some of them, it would be necessary to develop a model of minipopulus deliberation minimizing the risk of manoeuvring, and to think about the (very difficult) issue of the relationship between mini-populus and expertise.

Like

LikeLike

Andre:> To convert to dêmokratia these « scientists », or some of them, it would be necessary to develop a model of minipopulus deliberation minimizing the risk of manoeuvring, and to think about the (very difficult) issue of the relationship between mini-populus and expertise.

Agree, especially given the tendency of politicians to hide behind “the science” during the Covid-19 lockdown. “Normal” science is a highly disputatious and confrontational process (that’s why most journal articles are rejected at the peer review stage, even given triple-blind anonymity protocol). The only way to avoid manoeuvring is to adopt a similarly adversarial approach to policy generation, advocacy and expertise. It’s all very well saying we should leave it to the minipublic to select their experts, but how would they know where to look? Given that most people get their information from social media there is a real risk of ghettoisation, so the fears that Andre outlines about pseudo-science are very real.

LikeLike

> *** To convert to dêmokratia these « scientists », or some of them, it would be necessary to …

Forget it. This is an elite group that has little to gain from democratizing society. Sortition will gain ground by mobilizing the 99%, not by convincing the 1%.

> develop a model of minipopulus deliberation minimizing the risk of manoeuvring, and to think about the (very difficult) issue of the relationship between mini-populus and expertise.

Yes. Empowering the allotted to take advantage of expertise (rather than the other way around) is essential for creating a system that is in fact democratic rather one that pretends to be democratic but is in fact elite-controlled.

LikeLike

How should the members of a mini-public optimally distinguish true facts from definite falsehoods, and a third category of disputed knowledge? How should they select expert witnesses to consult? While Yoram has suggested a “laissez faire” approach, simply letting each member figure out who they trusted to consult. This clearly isn’t working in social media. But, might it work if getting their facts right REALLY mattered to the participants (unlike reposting tweets or “liking” posts on facebook)?

My solution is to have a separate mini-public charged exclusively with settling on a procedure for gathering factual information and expert witnesses for other mini-publics. They would decide on the “wholesale” PROCEDURE for screening, NOT the “retail” level of individual experts or facts. The key is to use the philosophic concept of the “veil of ignorance.” Those deciding HOW to select facts and experts do not know what topics, what experts, or what facts are under consideration. they cannot force their biases on particular issues into the procedure for fear that other biases they oppose will warp the process against their interests. To support the making of GOOD decisions, they have an interest in protecting the mini-publics from false information on ALL issues. (The members of a legislative minipublic tackling a specific issue would not benefit from this veil of ignorance, and its members would favor information that confirmed their prior biases.)

Admittedly there is a bit of a bootstraping issue in that the first such design mini-public, which will want to consult all kinds of experts on history, epistemology and science, but won’t have initial guidance on how to select THESE first tier experts for consultation. However, through repeated rounds of subsequent design mini-publics refinements can improve the information selection design.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Terry,

It’s certainly the case that your factual information minipublic would be operating behind a “veil of ignorance”, but not in any sense that Rawls would have approved of. Presumably you rule out peer review on principle as it is “elitist”?

LikeLike

*** Yoram Gat says : « Forget it. This is an elite group that has little to gain from democratizing society. Sortition will gain ground by mobilizing the 99%, not by convincing the 1%. »

*** Here we disagree. We cannot hope to convince and mobilize all the social elites. But we can convince a part of them, let’s say 20 %, and perturb the hostility of another part, leading it to indecisiveness.

*** In present day developed countries, the elites are not monolithic. Some high on the culture scale have few money and everyday life problems. Some think, rightly or wrongly, they did not get from the society which they deserved. Some with a scientific or technical training don’t like the social dominance of lawyers, media people, finance people. Some from their kind of upbringing or from political traditions don’t like so much the polyarchic model, as immoral or irrational. Etc …With possible compounding of factors.

*** It would be very difficult and dangerous to undertake a democratic mutation without having support of some fractions of the elites, and indecisiveness of others.

*** Actually, I don’t remember any historical case of successful political mutation without such a support from a fraction of the elites. A 21st century (ortho-)democratic mutation could be the first case ? Maybe, as the « third modernity » is different from past times, but I doubt.

LikeLike

Andre:> It would be very difficult and dangerous to undertake a democratic mutation without having support of some fractions of the elites, and indecisiveness of others.

Yes indeed, and the best way of avoiding manipulation is via public argumentation and conflict — let the various elites you describe argue their case and have the (mini)public decide which are the most persuasive. Why opt for Downsian rational ignorance or Rawlsian veils of ignorance when you can have your cake and eat it (elite advocacy and popular judgment).

PS it strikes me that Terry’s proposal for an allotted commissariat deciding who should be allowed to advise the people is closer to the current fashion for non-platforming than isegoria for the modern age.

LikeLike

*** Bouricius’ideas about the specific jury laying down procedures under a “veil of ignorance” are clearly good. For instance, a judicial jury must not invent rules for each trial, they must follow rules laid down by a legislative jury.

*** But there are some difficulties. First we must distinguish in a debate « experts » – selected for their specific knowledge, and « orators » who are to expound the different possible views, without selection of these views (isêgoria). In a judicial debate, the orators will be the prosecutor, the defendant’s advocate, representants of victims, others maybe. In a democracy, the orators must always be free (isêgoria) and tell what they want (if in a civilized way). So you cannot prevent an orator to quote scientific or pseudo-scientific statements by supposed experts, complaining that the expert himself was not allowed to be present. Alas, we know people with high achievements, including Nobel prize winners some say, who become cranky, fanatic or senile. Such a situation may lead to a difficult debate, with some jurors, specially the more paranoid streak, convinced they are manoeuvred.

*** Therefore I doubt it is possible to forbid a jury to hear a person they want to hear.

*** Second, if we have a collective expert – a section of the Academy of Sciences, or any scientific or technical body, specific rules must be added : their advices to juries must be voted with secret ballot and mandatory vote, to avoid pseudo-consensus. The jurors must be aware of the real dissensus.

*** Another kind of collective expert would be a panel of people allotted from people having a specific ability or experience.

*** It could be difficult for a jury to judge when there is no real scientific consensus. But it is the same for any political body, made from people who cannot be expert in everything.

LikeLike

*** Is peer’s review on principle elitist ? Keith asks. At least it is an elite phenomenon. With the connected risks.

*** Academic cliques – and blindness to names is not very efficient ; the clique may be easily discerned from references, vocabulary, themes.

*** Conservatism.

*** Conformism, specially when there is a pseudo-consensus fueled by ideological or social bias.

*** Well, I don’t deny the merits of peer’s review, but it has its limits, specially with subjects with strong political overtones.

*** The risks of peer’s review may be lessened by a good social structuring of Academic Research, aiming to limit the three risks. With plurality of research bodies around the same subject, but with people of different backgrounds.

LikeLike

Andre,

Agree, but we shouldn’t throw out the (elitist) baby with the bathwater, that’s why I’m attracted to your notion of a panel allotted from people having a specific ability or experience.

LikeLike

Terry,

> While Yoram has suggested a “laissez faire” approach, simply letting each member figure out who they trusted to consult. This clearly isn’t working in social media.

“Clearly” in what sense? Because social media users are showing deep distrust of establishment expertise? Such distrust seems very well justified. Because Russians prefer Putin over his Western-backed competitors?

Yes – the average person is not particularly informed. Being informed takes resources (money, staff) that the average person lacks, and time and effort that the average person has no reason to invest. That of course is why sortition is a better governance tool than plebiscites. But is there any reason to suspect that the average person is doing a worse epistemic job than can be done with the constraints imposed upon them?

The idea of having multiple bodies with differentiated roles (e.g., one body setting rules and procedures, another for making policy) is not problematic in principle, as long as all bodies are allotted from the entire population. That said, your assertion that the same group people that would happily set up rules to combat “false information” would fall pray to exactly such false information when tasked with making policy seems far fetched.

LikeLike

Andre,

> *** In present day developed countries, the elites are not monolithic.

They never were. Elite factions have always competed with each other in various ways.

> *** It would be very difficult and dangerous to undertake a democratic mutation without having support of some fractions of the elites, and indecisiveness of others.

Meaningful change is always difficult and dangerous. Those difficulties and danger are already upon us. To what extent these will become more extreme is hard to know, but the notion that these can be avoided by providing some arguments about how democracy is going to be great for the elites seems unrealistic.

> *** Actually, I don’t remember any historical case of successful political mutation without such a support from a fraction of the elites.

The following may be familiar:

That is, support by some parts of the ruling class is not an enabler of the change but is rather caused by the accumulating power behind the change.

LikeLike

Yoram,

Thank you for confirming the provenance of your view on the primacy of class interests (and the “accumulating power” of the revolutionary class) in Marxist dogma. For the benefit of those who are unfamiliar with the literature here’s the reference that you omitted to supply:

Marx, K. and Engels, F., Manifesto of the Communist Party, trs. Samuel Moore (Chicago: 1888), p.26.

Whilst some might still believe that Marx and Engels’ ‘scientific’ approach to political economy revealed universal covering laws, others would claim that they were merely reflecting contingent (19th century) historical factors and that the political sociology of “elite(s) vs. masses” is of no contemporary relevance. But thank you for making your position clear and enabling us all to see that there’s little point trying to argue with dogmatic claims like “support by some parts of the ruling class is not an enabler of the change but is rather caused by the accumulating power behind the change.” Just a the Pope will always be a Catholic however much he may shape shift, once a Marxist then always a Marxist, even if you express it in a different vernacular.

I do, however, agree with your critique of Terry’s multi-body sortition model as it makes little difference which group of randomly-selected persons does what. Ignorance is ignorance whether it is Downsian (rational) or the product of a Rawlsian veil.

LikeLike

*** Yoram Gat says « « support by some parts of the ruling class is not an enabler of the change but is rather caused by the accumulating power behind the change. »

*** Actually accumulating power behind a strong political mutation may induce support of some parts of the established social elites only if they have some reasons to join ; the same for indecisiveness. If this not the case, the elites will join forces, form a common front and crush any undertaking.

*** Let’s put aside any totalitarian movement, power taking by a militant sect. I don’t imagine such a movement leading to a (ortho)-democracy, giving power to ordinary people. Even supposing these militants idealizing democracy, they will find a pretext to postpone the day « when circumstances are good », « when the people is well conscientized » etc . …i.e. until « Last Days ».

*** In the last quarter of last century, we saw various authoritarian and totalitarian systems collapse, sometimes with disorder and reaction, but in various cases giving way to polyarchies. Therefore it is not absurd to imagine a mutation that would be towards (ortho-)democracy, directly or through an hybrid system. But such a phenomenon needs support by some fractions of the established elites and indecisiveness by other fractions.

*** Opinion polls in Western polyarchies seem to indicate that is not an absurd expectation. We don’t know about China.

LikeLike

Keith and Yoram agree that my idea of a separate allotted body deciding procedures for selecting expert witnesses and stipulated facts is unhelpful. As Yoram wrote:

>”your assertion that the same group people that would happily set up rules to combat “false information” would fall pray to exactly such false information when tasked with making policy seems far fetched.”

Here is a very brief explanation of why this design element is so vital.

Prior to being selected for a mini-public, people pick up all kinds of “facts” about some particular policy matters and develop biases. whether the topic is taxation, abortion, gun regulation, government monitoring of citizens, immigration, etc…. Many people chosen for a mini-public will effectively pre-judged the issue, and if asked who they should bring in as witnesses, many are likely to think of those celebrity “experts” they have seen on TV previously, etc. They may feel informed, even as they have completely neglected vital aspects of a well-balanced presentation, because they are focused on the TOPIC, rather than the process for how to be well-informed. The danger is that rather than becoming informed, the minipulbic members will replicate the misinformation process they went through in a warped media landscape before being drawn. They will succumb to confirmation bias, selecting “facts” and witnesses that confirm their prior beliefs.

However, if these SAME people had instead been placed on a mini-public charged with designing good rules for HOW to select witnesses and develop background fact sheets for future jurors dealing with unknown future topics, it is unlikely they will decide that that future mini-public should rely largely on celebrities who are TV in the future. Since they don’t know what topics will be on the agenda, let alone what celebrities may be popular, their incentive is to devise procedures that will accurately inform future jurors about bona fide facts.

It may be, as André noted, that issue mini-publics will also have the ability to call in favorite celebrity witnesses, but this should be discouraged if possible.

LikeLike

Terry,

> that issue mini-publics will also have the ability to call in favorite celebrity witnesses, but this should be discouraged if possible.

What about “activists”? Are they legitimate? Who is to determine whether a particular person is “a celebrity witness” or “an expert”? Are we going to rely on establishment credentials? Are these the kind of “anti-false information” rules that you would expect the “rules and procedures” body to set up?

Again, it is not that your proposal about having different allotted bodies tasked with different aspects of governing is necessarily a bad idea. But it must be up to the allotted themselves to design and improve the system. It is the notion that some elite group should set up rigid rules in advance for how democratic government should function that is bad. It is in fact an anti-democratic notion. Instead of allowing self-appointed, or establishment-appointed, experts to set up a detailed blueprint for a rigid system, a democratic system must be self-designing and self-re-designing.

LikeLike

Yoram:> It is the notion that some elite group should set up rigid rules in advance for how democratic government should function that is bad.

Agreed. Terry’s group would start off behind a veil of ignorance and would end up as an aleatocracy, plagued by a combination of caution (appointing, say, the Royal College of whatever as experts in a particular domain) and groupthink. The worst of all possible worlds.

Terry:> background fact sheets for future jurors dealing with unknown future topics.

Are you being serious? How can you have a fact sheet for the unknown unknowns?

LikeLike

*** I think we must stick to distinguishing « established experts » and « orators » – who may pretend to be experts, it is impossible to forbid it along isêgoria principle. « Established experts » are a kind of magistrates. They would be selected along procedures set by legislative juries. I agree with Bouricius here. But I don’t agree with Bouricius’idea « discouraging celebrity witness » : these must be accepted as orators, with isêgoria. Bouricius’ fear of jurors being easily tricked by good orators / celebrities is excessive, even if this is a risk we must accept it in democracy.

*** I understand Yoram Gat’s fear of « establishment-appointed experts ». But a democracy could lessen it by plural organizing of the research and by procedures of secret ballot and mandatory votes when a scientific body gives advice to the dêmos (even actual expert elites are not so monolithic as Yoram suppose, and it would be often possible to see when an apparent consensus is a pseudo-consensus resulting from social pressure).

*** As « established experts » are a kind of magistrates, they may be subject to a form of clearance (dokimasia) checking for instance if they belong to anti-democrat circles (it will be easy for a new ortho- democracy, more difficult maybe for an established one).

*** We may note that the problems we are discussing here are occuring with present judicial juries. Is glyphosate dangerous ? Is repressed memory real ? Difficult to decide for the ordinary juror in contemporary systems. But is it easier for elected or professional judges ?

LikeLike

Keith, To clarify… The mini-public charged with designing the information process for future mini-publics would not prepare any fact sheets, or lists of witnesses. Their role would be to settle on the procedures for selecting witnesses and preparing educational materials, etc. regardless of the topic (presumably with a professional staff they can hire and fire) that they believe will optimally inform future mini-publics on whatever topic they may deal with. They may decide to use university degrees, peer-reviewed publication reviews, to balance opposing experts, use surveys of a wide assortment of experts, random selection from a pool of qualified experts, or whatever. The design mini-public will be constantly refreshed through rotation and certainly constantly refine the process of selecting experts based on observing the quality of decisions being made, etc. It is simply my expectation that such a jury would not decide that celebrity and frequency of TV appearances is a useful metric.

LikeLike

Terry,

That’s all very motherhood and apple pie, but how would it work out in practice? Say, for example, there was a need for a minipublic to decide policy on Covid-19. They would look up their rule book and find that they need to get expert opinion from . . . people with university degrees. Although that reduces the field by a couple of hundred million, degrees in what subjects? Epidemiology or virology (would they know the difference?), immunology, public health, economics, education? And if they decided that epidemiology was the most important field would they know that (in the UK) there were two principal schools of modelling — Oxford and Imperial College and that both schools required equal representation? Given the random nature of your model it’s more likely that someone on the permanent staff happened to know someone from their time at Oxford who studied viruses and who probably knew who were the experts on the topic. There is some merit to the principle of random selection from a pre-qualified group, but you don’t need a minipublic to point this out, it’s more likely to come from our little elite group of kleroterians.

Let’s take another example, the Bletchley Park team that cracked the WWII Enigma code. This has been famously celebrated (by Helene Landemore and others) for its “diversity”, as it included archaeologists, mathematicians, cryptologists, Egyptologists and crossword puzzle experts. Would your procedural minipublic have come up with such a list? I doubt it, they would have probably played safe and left it entirely to mathematicians and naval signalling officers (the Enigma machines were used by U Boats). Chances are the diversity was created by some Oxbridge type who recalled sitting down to dinner at Balliol with a (brilliant) group of archaeologists, mathematicians, Egyptologists . . .

LikeLike

>>> Keith

*** Difficult maybe for a democratic sovereign dêmos to know which experts to hear and trust about an epidemy. But are you sure it was very easy for today polyarchic or autocratic governments ?

*** The advantages of diversity may be understood by a sovereign dêmos. Actually the idea of diversity among councillors may be accepted more easily by regimes with a true sovereign, monarchic, aristocratic or democratic, where expertise and power are separated, whereas in polyarchies and autocracies the political elite disguise themselves as some kinds of « general experts » ( !) « who know better ».

*** Is the success of the « Bletchley Park team that cracked the WWII Enigma code » linked to polyarchy itself ? Maybe it was more linked to the residual aristocratic element in the British system.

LikeLike

> But are you sure it was very easy for today polyarchic or autocratic governments ?

Indeed, this is another reason why this whole endeavor of making sure that the allotted do not act “irrationally” betrays a deep-seated anti-democratic sentiment.

The concern about proneness to irrationality that is attributed to the allotted is hardly ever brought up in other contexts of decision making. Do we ever hear it suggested that elected officials, business top officers or generals must be bound by certain rules regulating the way they make decisions or who they consult with? No – it is always the hoi polloi who are supposedly always merely a step away from becoming an irrational mob, who can be easily swayed by slick talkers, celebrities, demagogues, or just be swept away by an innate racism and closed mindedness, into making irrational decisions.

Such rhetoric claims to be about rationality but in fact is underlied by an elitist mindset according to which normal people cannot be trusted with power unless tutored, or handles, or guided, or restrained by the responsible adults in the room.

LikeLike

Andre,

I agree that the issue of expertise is difficult for a democratic sovereign and suspect you may well be right about the “aristocratic” selection process for the the Bletchley Park codebreakers. Lord Carrington (Margaret Thatcher’s foreign secretary) told me some years ago that the unreformed House of Lords (he inherited his seat in 1940) was much more diverse — both occupationally and cognitively — than its polyarchic replacement.

I agree, of course, that expertise and sovereign power should be strictly separate, that’s why Alex and myself advocate distinct appointment methods for each. I think Terry is wrong to claim that this is possible by assigning distinct functions to different groups of randomly-selected persons.

Yoram,

The point is not that hoi polloi are an irrational mob, just that it’s implausible that the selection of balanced expert advocacy would emerge spontaneously from people who don’t even know where to look. As a result they will be swayed by people who sound as if they know what they are talking about, even if — as Andre claims — this is just a disguise.

LikeLike

Yoram observed that:

>”The concern about proneness to irrationality that is attributed to the allotted is hardly ever brought up in other contexts of decision making.”

This is sadly true. I have written an entire book manuscript (still can’t find a publisher) devoted to why elected representatives are the LEAST suitable group for making public policy decisions. Yoram is most concerned about electeds tending to promote their self-serving interests that diverge from the majority of the population. While I agree with his point, there are other problems that make them unsuitable even when their interests might align with the population’s. The vast array of psychological dynamics is too long to go into in this comment, though perhaps i can make a stand-alone post some time that hits the high points. However, my concern is that although many of the dynamics that make elected representatives horrible representatives will automatically be mitigated through the use of random selection, there are also some of these dynamics that will likely be replicated in an allotted body if its procedures are not carefully thought through in advance (by members of a mini-public with a focus on procedural issues rather than policy issues). In short, I do not think the hoi polloi are more prone to irrationality (indeed less so), but poor design (for example one that keeps the typical design of an elected chamber but simply swaps out the elected members with randomly selected members) will not allow an allotted chamber to achieve its best potential.

LikeLiked by 2 people

Sounds pretty interesting and important Terry

Any chance of sharing some of the contents of the book here or privately via email?

LikeLike

Terry:> poor design (for example one that keeps the typical design of an elected chamber but simply swaps out the elected members with randomly selected members) will not allow an allotted chamber to achieve its best potential.

Quite so. Allotment and preference election are entirely different forms of representation (and to claim that one is “more representative” than the other is a category error). The design (and mandate) of an allotted chamber would need to reflect the difference.

LikeLike

Terry,

> but poor design (for example one that keeps the typical design of an elected chamber but simply swaps out the elected members with randomly selected members) will not allow an allotted chamber to achieve its best potential.

Fine, but why do you tie those two issues together?

Tying the issue of sortition with the issue of optimal procedural design really confuses the issue, even if inadvertantly. The implication is that the allotted cannot be trusted with as much power as the elected are and that the two reforms – replacing elections with sortition, and separating procedural powers from policy powers – must be made in parallel or else the confused and naive allotted delegates will bring us to ruin.

Wouldn’t it be much more straightforward to say: “let’s replace elections with sortition, and then expect the allotted themselves to redesign the system in a way that they think works best”?

LikeLike

Yoram:> The implication is that the allotted cannot be trusted with as much power as the elected.

Not so. The implication is that these are two fundamentally different types of representation, and this is the domain of (elite) political theorists and constitutional lawyers, not hoi polloi. I imagine you will retort that elected politicians are equally unqualified according to this criterion, however they have been chosen by citizens to represent them, whereas all you can say about an allotted body is that, if of a sufficient size and constituted by a quasi-mandatory allotment, that the aggregate votes of such a body will track the population that it is intended to describe.

LikeLike

Nicholas,

I don’t think I can easily condense what I take several chapters in my manuscript to argue, down to a Blog post. I would be willing to send you text from my rough draft, if you commit to some sort of copyright protection (I still want to publish this under my name). Send me an email to terrybour(at)gmail.com. If I get motivated, I may try to make a condensed summary, but worry that without all the substantive explanation of research and citations, it will just come off as a bunch of assertions, which contradict 250 years of hardened electoral mythology.

LikeLike

*** Keith says « Allotment and preference election are entirely different forms of representation (and to claim that one is “more representative” than the other is a category error). »

*** The best would be to avoid to use the word « representation » and « representative » (except with the scientific meaning of representative sample). Either the last word is given to the populus, or a mini-populus mirroring the populus, and it is democracy (or ortho-democracy). Or we have the polyarchic model, with election of parlementarians along very diverse procedures and complex appointing of high judges. We can discuss these two models without using the word « representation », which leads us into byzantine debates.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Andre,

Unfortunately the ongoing political theory debate (Pitkin, Manin, Urbinati etc) is on the nature of representative government. Pitkin’s book is still the uber text on political representation and the arrogation of the last word to a minipopulus is dealt with in just one chapter out of ten. That’s why I’m in favour of your neologism “stochation”. If Terry et al still insist that randomly selected persons are “more representative” than elected politicians then I will need to keep reminding them that they are misusing the term, otherwise we are all going to look very silly. Much better to claim that a randomly selected body better “describes” (in aggregate) its target population than to say that randomly selected persons are more “representative”. We can’t just ignore the debate on representative government we need to engage with it, but in a manner that respects the existing use of words.

LikeLike

Within THIS micro-realm we could possibly agree to talk about elected bodies as pseudo “agents” of the population, and mini-publics as “statistical samples” of the population to avoid using the word “representative.” But why bother? In talking to the rest of the world I think we are stuck with the terminology of better or worse forms of “representative democracy.” When a subset of people are unlike the people and have significant persistence over time we agree on using terms like oligarchy or aristocracy… so we can debate whether electeds are more akin to oligarchy or representative democracy, and whether rotating mini-publics fit the vision of democracy.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Terry,

That presupposes, of course, that it’s an either/or dichotomy. Alex and I have argued that there never has been a unitary system of governance (outside dystopian fantasies, some of which have been put into practice) and that democracy requires a combination of election and sortition. And the word “pseudo” is a tad pejorative. For the sake of clarification the word “oligarchy” doesn’t (unlike aristocracy) presuppose a lack of similarity between the rulers and the ruled, as it is simply the rule of the few. Rule by a few randomly-selected persons is a form of oligarchy, not democracy.

As for “this micro-realm” I would prefer for us to engage in a form of discourse that is comprehensible to others beyond our little magic circle. The best way of doing that is to use language in the same way as everybody else.

LikeLike

Andre,

> *** The best would be to avoid to use the word « representation » and « representative » (except with the scientific meaning of representative sample).

I don’t see why we need to abandon the word “representative”. When you say that a sortition-based government is “democratic”, it is not just a tautology. You are asserting that sortition-based government has some desirable, democratic, properties. What are those properties?

The only useful (non-technical) meaning of “representative” in the discussion of government is representation of interests and values. A democracy is a government which the population believes pursues, or “represents”, the public interests and values – in this sense democratic government can be defined as “representative government”. All other meanings (“modes of representation”) are a diversion (deliberate or not).

LikeLike

Yoram:> A democracy is a government which the population believes pursues, or “represents”, the public interests and values

If so then Germany in the 1930s, modern China and (possibly) North Korea are democracies. Note that this is also a definition that Hobbes would have been happy with (not that he was a fan of democracy) as it legitimises a single person (or party) as the legitimate sovereign. And your definition is orthogonal to the democracy/oligarchy/monarchy axis.

Are you able to find a single democratic theorist who shares your view?

LikeLike

*** Yoram says : « All other meanings (“modes of representation”) are a diversion (deliberate or not). » He may be often right (allowing for some honest intellectuals !). But, precisely, accepting to entering into debates about the many senses of the word « representation » is giving free way to those who are looking for diversion.

*** Democracy is the system where the dêmos rules either by general vote or by allotted juries (the second way being inevitably the main one in a modern dynamic society, given the amount of political work). This was the definition by the people who created the word dêmokratia, without even having the idea of any of the twelve concepts of representation. (I propose the word ortho-democracy only in cases where it is necessary for clarity).

*** Terry says : « In talking to the rest of the world I think we are stuck with the terminology of better or worse forms of “representative democracy.” ». I discussed with various people of different ages and social class about the democracy-through-juries model. I encountered various arguments : about low political ability of the jurors ; about gullibility or bad impulses of some (low) classes ; about the depolitizing effect ; about the canceling of the right to choose a policy through the election of the President (apparently the one significant election in France !). I don’t remember any occurrence of « representation » from any opponent. Well, it is France, with its specific tradition. But is Terry sure that discussing with ordinary Americans they will introduce any concept of representation if he does not begin ?

*** Keith says « Unfortunately the ongoing political theory debate (Pitkin, Manin, Urbinati etc) is on the nature of representative government. Pitkin’s book is still the uber text on political representation ». Precisely I think we should avoid entering this debate, and try to open other debates. Intellectual advances may occur by opening new debates rather than rehearsing old ones.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Andre:> Democracy is the system where the dêmos rules either by general vote or by allotted juries.

Agreed, the criterion being ruling, as opposed to the perceived representation of the interests/values of the masses, which can be realized by non-democratic institutions.

> I think we should avoid entering this debate [on representation]

Then we should stop using the term, and replace it with neologisms like stochation. But then this means we only get to talk among ourselves. What we can’t do is take a term in existing use and then just ignore the myriad forms of representation — this will just make us look lazy or myopic (i.e. we can’t be bothered to read the literature). It also makes us prone to errors like Terry’s claim that oligarchy is when the rulers are unlike the ruled — the term “oligarchy” is in fact quantitative rather than qualitative. At minimum we have to apply adjectives like “descriptive” or “statistical” and then accept the constraints that follow — i.e. that such a form only applies to collective actions, rather than individual speech acts (as pointed out by Pitkin). This leads to the corollary that statistical representation cannot on its own be a democratic form of governance.

QED

LikeLike

Keith,

You invented a definition that you attributed to me, “Terry’s claim that oligarchy is when the rulers are unlike the ruled.” I didn’t say that. I did not claim that being unlike the population was a _necessary_ condition to have an oligarchy (let alone sufficient). I wrote that when a persistent small group that is unlike the people rules, we are agree to put such a regime into the oligarchy category. That is one example of a regime that would be deemed oligarchic, not the definition. Attributing concepts, motivations, hidden analytical frameworks (like Marxism) to other commenters is counter-productive.

LikeLike

Keith,

Note also that I wrote about “oligarchy OR ARISTOCRACY.” That second term DOES have a difference from the population as a necessary piece of it.

LikeLike

Terry,

Yes, I acknowledged that aristocracy does presuppose that the rulers are different from the ruled, but your “when a persistent small group that is unlike the people rules” implies that if the group was like the people then it would not be oligarchic. We both agree that a small quasi-mandatory randomly-selected group might well start of being like the people but, over time (i.e. “persistent”), would cease to represent the people descriptively (or in any other way). If so then being “like the people” is irrelevant. As for attributions of Marxism, you have always acknowledged your own background on the hard left and Yoram quoted approvingly from The Communist Manifesto in his recent comment (but failed to cite the source), so I don’t think the analytic framework is very deeply hidden — especially given his total focus of the opposing interests of the elite and the masses to the exclusion of any other consideration. Us country yokels from rural Devon like to call a spade a spade.

LikeLike

Andre,

> general vote

I don’t believe that the Greek texts we have describe the act of voting in the Assembly as a characteristic typical of democracy. Indeed it would be surprising if they did as it was part of the decision-making process in Sparta.

> Democracy is the system where the dêmos rules

Yes – but what this means exactly was left, at least as far as we know, rather vague theoretically speaking. Whatever theory there was (or at least whatever theory reached us) seems unsatisfactory. Presumably “democracy” was recognized through custom and practice rather than theory. Since this is also largely the modern situation, maybe the lack of theoretical specificity is not surprising.

However, the Athenian “democratic” practice was to a large extent democratic (although it is likely that the elites had much more than their fair share of power), so their lack of theoretical development was not a fatal flaw. Modern “democratic” practice, on the other hand, is wholly oligarchical and so it is necessary for democratic activists to develop and promote a democratic theory in order to undermine the established practice and point the way to a democratic one.

LikeLike

Yoram:> I don’t believe that the Greek texts we have describe the act of voting in the Assembly as a characteristic typical of democracy. Indeed it would be surprising if they did as it was part of the decision-making process in Sparta.

The difference between Athens and Sparta was ho boulomenos — anyone could make proposals and offer advice before the vote took place. Hansen and others argue that Athenian democracy was a combination of isonomia and isegoria (Sparta only had the former). Most historians also agree that the function of the randomly-selected council was to protect the sovereignty of the assembly.

LikeLike

*** Yoram Gat says: “ I don’t believe that the Greek texts we have describe the act of voting in the Assembly as a characteristic typical of democracy. Indeed it would be surprising if they did as it was part of the decision-making process in Sparta.”

*** Actually anti-democrat texts mostly underlines the Assembly role and minimize the jurors’ role, specially about judicial review – we could not imagine it from Aristotle, without the orator texts. The assembly debates were more usable in the anti-democrat discourse about “the irrational and reckless mob”.

*** As for democrat theory, yes, Theseus in Euripides’ Suppliant Women develop a little more the sortition theme. He had to do it, because it is less self-evident as a channel of popular sovereignty: he says that the demos reigns/rules through annual successions (that the annual panel of jurors was not biased by Luck is implicit, but could not be demonstrated by lack of statistical theory).

*** As for the general vote in the Assembly, it had not to be expanded on, because it was so much self-evident power of the People. Actually in political language the word “demos” did not mean only the civic body but likewise was the current technical word for the assembly: in the Second Athenian Democracy the laws were said “decided by the legislators = nomothêtai “ (subject of academic debate), the decrees “decided by the assembly = dêmos”.

*** I don’t think there was much idea in Athens about canceling the Assembly and giving all power to allotted bodies or to fractions of the civic body by turns. Aristotle mentions such an idea by Telecles of Miletus (Politics IV, 14, 4; 1298a12-13). The main subject of 4th century Athenian assembly was peace and war, and the Assembly roughly was the assembled fighting citizen body.

*** The role of jurors grew in the Second Athenian Democracy, and was very strong in Demosthenes’ time, but in 5th century it was a lesser element of the democratic system. When the components of the word “dêmokratia”, if not the word itself, appear in Aeschylus ‘Suppliant Maidens” (v 604-5), probably not long after the democratic mutation, it is about a vote in the assembly. To the question of his daughters about the vote about their fate: what decided “the sovereign hand of the People (dêmou kratousa cheir) expressing the majority” ?, Danaus answers “action was taken by the Argives, not by any doubtful vote but in such a way as to make my aged heart renew its youth. For the air bristled with right hands held aloft as, in full vote, they ratified this resolution into law”. This first appearance of democracy in Greek literature refers to the hand vote in the assembly, not to the token vote by jurors.

*** Classical Sparta was not considered as a democracy, even if the popular assembly had some real power. We don’t know well the functioning of the Spartan Republic, but the undemocratic points of the system must have been the procedures of the assembly and the power of other bodies as the elected (for life) Council of the Elders which Demosthenes denounces as oligarchic in “Against Leptines” (107-108). Ancient oligarchizing republics, as the Spartan one and the Roman one, included “popular” elements without being democracies. Modern polyarchies likewise may include general suffrage or referenda, without being democracies: these elements are included in systems which are usually efficiently antidemocratic, even if at the beginning there were strong elite fears about these elements. Some polyarchic bold ideologues, as Rosanvallon, intend to do the same thing with well-designed allotted panels, used against popular dissent.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Andre:> in the Second Athenian Democracy the laws were said “decided by the legislators = nomothêtai “ (subject of academic debate)

We shouldn’t underestimate the extent to which Mirko Canevaro has undermined our view of fifth century Athens as a sortition democracy. Daniela Cammack has just reviewed a paper that Alex and myself are working on and her advice is that we should drop all reference to the nomothetai as a randomly-selected body (Canevaro’s claim is that it’s just the assembly wearing a different hat). If this is true (and the jury is still out) then fifth century Athens was a direct mass democracy (with judicial checks and balances) in which randomly selected bodies had little or no role to play in the legislative process. This is (from my perspective) highly unfortunate, but we can’t distort the historical record to suit our own pet theories. Needless to say none of us on this forum (with the possible exception of Andre) are remotely qualified to adjudicate this dispute (essentially between Mirko and Mogens). I put it to Mirko that it might need another arm-wrestling match, as in the argument between Hansen and Ober. I don’t know who won the original match, but age (unfortunately) favours the young.

LikeLiked by 1 person

André,

> *** Actually anti-democrat texts mostly underlines the Assembly role and minimize the jurors’ role, specially about judicial review – we could not imagine it from Aristotle, without the orator texts. The assembly debates were more usable in the anti-democrat discourse about “the irrational and reckless mob”.

I agree that the Athenian Assembly was pilloried by the aristocrats. However, the emphasis was (and indeed had to be) not on the voting stage (which occurred in non-democratic Sparta as well), but on proposing and debating stage – on the fact that unworthy people (whether selected at random or self-selected) were given a platform to offer proposals and arguments to the Assembly. It was not mass voting but the notion that the hoi polloi are allowed to take active political roles that was abhorrent to the aristocrats.

The Socratic argument against sortition, for example, assumes at the outset that the masses are able to recognize the master flutist. Their choice to listen to the master flutist is analogous to voting for the master statesman or to prefer the proposal of one aristocrat to that of another. In contrast, the idea that just anyone has the right to speak in front of the Assembly seemed to Socrates as absurd as the idea that just anyone has the right to play the flute in a concert hall.

Of course, this ideology is still going strong among modern elites. The notion of political power being wielded by average people still invokes among many supposed democrats, including many supposedly democratic reformers, those same horror and amazement they invoked in Socrates (even if modern ideology makes many of those moderns hide those elitist sentiments behind much more convoluted and mendacious rhetoric).

LikeLike

>> Keith

*** I shall not adjudicate the dispute between Hansen and Canevaro about the Legislators. Both have strong arguments, and we have no data which would allow us to decide. And maybe a third solution, as in some ancient scholiasts. It is something strange, but we don’t know about an important institutional item for the Athenian times we have most data about. In such a case of basic doubt, the opinion among historians could evolve along factors of academic clique, political trends, fashion … It is better to acknowledge “we don’t know”.

*** You say that following Canevaro “fifth [I suppose fourth] century Athens was a direct mass democracy (with judicial checks and balances) in which randomly selected bodies had little or no role to play in the legislative process”. I don’t remember such words from Canevaro. He did never deny the very strong power of jurors who could crush any decree as illegal, any law as inexpedient ( contrary to basic values or principles or interests) – and punish the proposer. Even this minimal model gives a big share of legislative power to jurors.

LikeLike

**** Keith Sutherland mentions Hobbes about the evaluation of modern (20th, 21s centuries) political systems, among them China.

*** Hobbes and Bodin were absolutist theorists: against disorder and civil war (a hard contemporary reality), power must be given to one person, to a sovereign. A collective sovereign (aristocracy, democracy) or an individual one (monarchy).

*** Their class bias were sufficient to put them against the democratic choice. And anyway democracy was impossible in big States before modern technology. Maybe there was a possibility in some remote Alpine valleys, and Bodin was intellectually interested by the Grisons (I don’t know for Hobbes).

*** They could not be fond of any system which, as polyarchy, has built-in conflictuality (polyarchy is not plutocracy, even if the moneyed elite has strong clout); or of totalitarian systems, which are institutionalized civil wars.

*** But China is no more a totalitarian system, it is an autocratic one, where a political elite has power without institutional balance, and boasts about practical results. Could Hobbes and Bodin have found some merit in such a regime?

*** This is not pure intellectual musing. The Western elites mostly criticize the Chinese political system, sometimes demonize it. But, under that, I am afraid there is some fascination for it. Maybe, if there was a choice between (ortho-)democracy and Chinese-style autocracy, some fractions of Western elites would choose the « efficient and rational and meritocratic » Chinese system (personally I am not sure it is so much efficient, rational and meritocratic).

LikeLike

Andre,

Agreed, that’s why I said “with judicial checks and balances” as the juries could overturn illegal and inexpedient laws and decrees. But (according to Canevaro) the laws were not made by juries.

I sincerely hope he’s wrong.

LikeLike

Why we don’t know about the 4th century Athenian Legislators?

*** When Demosthenes, asking for a change in the law about military funding, tells the Assembly: “You must convene Legislators”, he does not indicate who are these Legislators – because the members of the Assembly knew that ! Thus the orators do not inform us (the inserted quotations of laws are suspected not to belong to the original texts).

*** But Aristotle, “the political scientist” ?

*** Nothing in the “Constitution of Athens” – some say: because we lost a part of the text.

*** Nothing in the “Politics”. Some say “because it is a general study, and not interested by a specifically Athenian institution”. Frankly, I doubt. Or “because it was not important, only a procedural name for the Assembly as usual”. Aristotle could have mentioned the name, he was teaching in Athens.

*** We must remember that Aristotle forgets likewise the “graphê paranomon”, procedure of illegality, so important in contemporary Athenian political life, as we know from orators (he mentions it only laterally about the philosophical debate on slavery). He omits it because he wants to omit everything which does not tally with his view of democracy as rule of a reckless mob.

*** We must conclude that the Legislators were something specific. A jury, as thought old commentators. Or an Assembly, then following very specific rules. Or ? An ancient commentator said it was a set including a jury and the Council !

*** We don’t know. But we must remember that Aristotle is a political scientist we cannot trust.

LikeLike

Yes, we just don’t know, and I think the absence of evidence might favour Mirko’s interpretation — to change the rules for approving new legislation from everyone to a small allotted sample is a major innovation and yet there is no evidence recording any opposition to it. If Aristotle believed that juries were even more democratic than mass voting, you think he might have mentioned this constitutional innovation. And there’s certainly no evidence to support the view that majority voting in the assembly was not a key characteristic of Athenian democracy. Bear in mind that nomothetai (whoever they were) could not be assembled without an assembly vote.

LikeLike

André,

Perhaps you know more about this than I. I read that the biographer/historian Plutarch wrote that in Athens the jury was sovereign (rather than the assembly). Presumably this was because a court could overrule the Assembly as you note. But could he have also meant the nomothetai?

LikeLike

We should remember that Plutarch was writing from Rome, some 400 years after the events that he was describing. Did he know anything that modern historians didn’t and was he doing anything more than popularising Platonic and Aristotelian perspectives on Athenian democracy? Is it even accurate to refer to him as a historian (rather than a moralist)?

LikeLike

Andre:> An ancient commentator said it was a set including a jury and the Council !

That’s a very strange notion, who was the commentator? How did the two bodies interact?

LikeLike

Terry

*** Plutarch is very late writer, and we don’t know his sources. It is doubtful he had knowledge about who were the Legislators. If the quotation of laws inserted in orators ‘ speeches, and which indicate Legislators as some kind of jurors, were not in the first editions, and were added later, either these later editors of the speechs knew the truth from their own sources, that would imply the Legislators were jurors; or they imagined it from plausibility: Demosthenes asks the Assembly to convene the Legislators -Olynthiac 3, 10 -, therefore they must be different, therefore they must be jurors. If this is the case, they did not know the truth, and probably Plutarch did not know it either.

*** The very strong power of allotted popular juries in 4th century Athens was known by Plutarch and Hellenistic/Roman historians, from the Attic orators and philosophers. And maybe they were specially struck by it because it appeared so much specific of democracy, and so much foreign to oligarchizing republics as the Roman one. Some historians think that the archeological remains of “kleroterion” in Athens, very late, did correspond to a time where there was a kind of (real or phantasmal) revival of the democratic model – in a world where the oligarchizing republic model had become the hegemonic model for Cities.

*** Being dikastês and ekklesiastês were the two ways for an Athenian citizen to participate as “kyriotatos” (Aristotle, Politics, ,III, 1,7;1275a25), it was the two channels of popular sovereignty, and we don’t know to which channel belonged the specific institution of Legislators mentioned in 4th century speeches.

*** Anyway the two channels were both the realities in the forefront of the political life of 4th century Athens. Whatever we think relevant for a 21st century ortho-democracy – in a very different world, where copying exactly Athens cannot be the rule – we must not project our drafts on the ancient city, and minimize one of the two channels of popular sovereignty in 4th century Athens.

LikeLike

Keith

About a strange ancient idea concerning the Legislators

*** Sorry, I have not my files where I am confined. I will give my reference when I am able.

*** I doubt strongly about the seriousness of the idea. Rather evidence that Hellenistic commentators were in the haze.

LikeLike

Andre:> we must not project our drafts on the ancient city, and minimize one of the two channels of popular sovereignty in 4th century Athens.

Agreed

LikeLike

Keith

Sorry, what, by lapse of memory (I don’t have my files), I said was an ancient interpretation of the Legislators as [jury + council] was actually a modern one by MacDowell, interpreting (probably wrongly) a document (Epicrates’ decree) inserted in Demosthenes Against Timocrates (28) – which is anyway probably an ancient forgery !

Better forget, there is sufficient mist.

Modern as ancient commentators are wandering by lack of sure data.

LikeLike

*** Yoram says: “The Socratic argument against sortition, for example, assumes at the outset that the masses are able to recognize the master flutist. Their choice to listen to the master flutist is analogous to voting for the master statesman or to prefer the proposal of one aristocrat to that of another. In contrast, the idea that just anyone has the right to speak in front of the Assembly seemed to Socrates as absurd as the idea that just anyone has the right to play the flute in a concert hall.”

*** We must consider something strange. The Socratic argument is aimed not to the sortition of jurors, but to the sortition of magistrates, whereas actually the allotted magistrates had few political power, and therefore were not a very logical target for a philosopher putting the idea of ability in the debate.

*** First explanation. The magistrates have more specialized “technical” functions, therefore the ability argument is easier to use: “the magistrates overviewing finances, maybe they don’t know how to count”. The criticism belongs to a general “anti-democrat ability discourse”, but chooses the easier target.

*** Second explanation, the juries are one of the two channels of popular sovereignty, and the philosopher does not want to attack openly the heart of democracy. He prefers indirect attack.

*** Third explanation, following Yoram: the ordinary citizens are not able to decide, but they have a somewhat higher ability to choose the deciders. It is the idea of “elective aristocracy” that we found in the Western Enlightenment, before the domination of the “representative” idea.

*** Fourth explanation, following likewise Yoram, the idea of an elite control of political proposals, against isêgoria. Actually a rule of monopoly would not be practical, no elite is perfectly homogeneous: think of a law in 19th century Britain giving the monopoly of political proposals to the capitalist elite, not a problem, Engels was a member of the capitalist elite. But we may imagine a control of proposals (and of debate) by some kind of Council of Wise Men akin to the elite. We find nowadays in France such ideas in political debates about referenda.

*** Maybe it is not necessary to choose among the interpretations. All may be good, and blend into a general “anti-democrat ability discourse”, strong in the Socratic circles.

*** This discourse led to two models: either the political ability is a kind of specific and superior technical ability, and we come to the Plato’s idea of “philosopher kings”, or it is a general ability linked to “culture”, and we come to an oligarchy, or rather, more realistically, to an oligarchizing republic along Aristotle. Modern anti-democrats are more on Aristotle’s side.

*** Protagoras seems to have answered by considering that there was a political ability, different from the technical ones, the basic elements of which were the moral and intellectual common senses, both widely distributed by Zeus, and not restricted to the elite.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Andre,

> the allotted magistrates had few political power

Assuming Xenophon’s account is reliable, then it appears that this view was not shared by Socrates’s audience (nor by his accuser’s audience – the jury in Socrates’s trial). Otherwise the punch-line of the argument – “no one would care to apply [allotment] in selecting a pilot or a flute-player or in any similar case, where a mistake would be far less disastrous than in matters political” – would not make sense. The argument hangs on the notion that the magistrates hold great power by handling “matters political”.

And indeed, unless you exclude the Boule from the category of “magistrates”, I am not sure how you can make the claim that the magistrates had little political power. The Boule, by setting the Assembly’s agenda and presenting proposals, had great influence over the Assembly’s decisions. Socrates’s aim was not being oblique – the Boule, by wielding the agenda setting power (and quite likely other executive powers) was the most powerful democratic element of the Athenian system.

LikeLike

Yoram:> the Boule, by wielding the agenda setting power (and quite likely other executive powers) was the most powerful democratic element of the Athenian system.

Your assumption being that the sovereign assembly was not democratic?

LikeLike

Yoram

*** Maybe the Boulê had more power than evaluated by many historians, because of its importance in the everyday functioning of the system, which is easily underestimated. But “the more powerful democratic element”, frankly it is difficult to accept. Assembly and juries in different fields had the last word, not the Boulê.

*** The councillors were magistrates (they underwent clearance, dokimasia), but of a very specific kind, not corresponding to a “technical” task, as fluteplayer or pilot. They could be only indirect targets of the Socratic discourse.

*** I acknowledge allotted magistrates had power, but second-level compared to jurors. Taking them as targets was disingenuous.

*** In our contemporary polyarchies, which stick more or less to their democratic myth, the elitist anti-democrat discourses are often oblique, likewise.

LikeLike

Andre,

The focus on the Assembly and the juries as “having the last word” is conventional, but it is mistaken nonetheless, IMO. If that was the right place to focus on, then it would be hard to explain why Sparta was not a democracy as well.

Being mass political bodies, the Athenian Assembly and juries had a role that is analogous to that of the electorate in a modern Western country. Their last word was about deciding between the options put before them. If those options are completely controlled by the various factions of the elite (as they were in Sparta, and as they are in a modern Western country) then that “last word” matters little. Coke or Pepsi?

The “last word” only becomes meaningful when a democratic body can put items – topic and proposals – on the agenda. That is the crucial difference separating Athens from the Spartan and the modern oligarchies. The Athenian Boule’s ability to put items on the agenda turned the formality of the Assembly’s last word into a meaningful device.

Unlike moderns with oligarchical sympathies, Socrates was explicitly and unashamedly “aristocratic”. Unlike them, he was not mincing words. He aimed his criticism at that component of the system that mattered most. Why would he be bothered by the Assembly and its “last word”? His beloved Spartan system had the Assembly having the last word as well.

LikeLike

Yoram:> it would be hard to explain why Sparta was not a democracy.

Historians (“conventional” or otherwise) agree that the reason Athens was a democracy, unlike Sparta and the Roman Republic, is because in a democracy anyone could make a proposal and speak in the assembly. The fact that most proposals were submitted via a randomly-selected magistracy is neither here nor there, although this did, in practice, help protect the isegoria/ho boulomenos principle from being undermined by factions. You may not like it, but 5th century Athens was a mass direct democracy (and if Mirko is proved right this was also the case in the 4th century).

LikeLike

*** Yoram Gat says: “Unlike moderns with oligarchical sympathies, Socrates was explicitly and unashamedly “aristocratic”.”

*** We don’t know directly Socrates. We know his political leanings through Xenophon and Plato, who were foes of democracy and might have turned the Socratic political discourse into something harder. It is doubtful Socrates was the head of an ideological anti-democrat sect. His more ancient disciple, Chaerephon, (satirized with Socrates in Aristophanes’ Clouds) was on the democrat side in the civil war between democrats and oligarchs (Socrates being actually neutral). Socrates was known to attract young elite people, but likewise to speak to any citizen he encountered. It would not have been easy for him to be openly against democracy. Unashamed aristocratic discourse was for elitist more closed circles. (We have two kinds of materials in our Athenian literary legacy: the open one – public speeches and theater – and the elitist circles one).

*** We don’t know directly Socrates, and we have only plausibility. My guess: Socrates was part of the Athenian counter-culture, where criticisms of democracy flourished (but not always in ideological sects), and he developed specially the issue of “political ability”, but avoided taking a direct political stand – which was easy along the intellectual style: ‘” I am not a knowing person, only a questioning person”. Bringing critically the subject of the allotted magistrates conveyed the issue of political ability without attacking the direct channels of popular sovereignty, as juries.

*** Well, I acknowledge other guesses are possible about Socrates. But I think anyway that for us, 21st century kleroterians, the more interesting is to consider the issue of “political ability”, which is, today, one of the main arguments against the mini-populus model.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Andre,

> interesting is to consider the issue of “political ability”, which is, today, one of the main arguments against the mini-populus model.

Meritocracy is the last refuge of the elitist. But, as I pointed out some years ago, meritocracy is inconsistent with elections as well. It is a remarkable fact that no reasonable model of political ability can justify the use of mass elections as a democratic device. One needs to either reject democracy outright (as Schumpeter did) or come up with quite convoluted theories of human behavior in order to justify elections.

LikeLike

Yoram:> convoluted theories of human behavior in order to justify elections.

How about people getting to choose who gets to rule, both on the basis of personality, policy and perceived competence? It may not work perfectly in practice, but it’s hardly “convoluted”.

LikeLike