The French discussion of “participative democracy” has recently produced several texts expressing suspicion of the way “participative devices” are being used by government to produce supposedly democratic outcomes.

Guillaume Gourgues writes in la vie des idées:

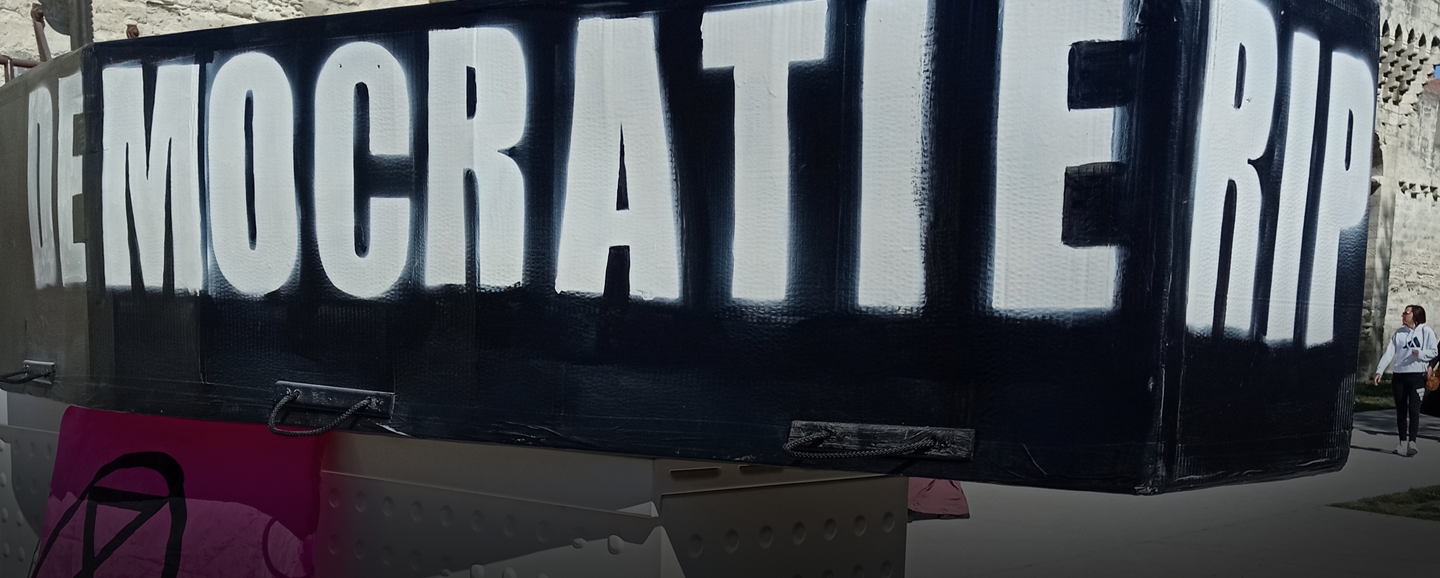

By setting up citizen consultations that it selects and organizes itself, the State sidesteps democratic procedures and institutions. There is the risk of a gradual drift towards a form of “participatory authoritarianism”.

On March 22, 2023, as he began his speech in the face of protests over pension reform, Emmanuel Macron defended the legitimacy of his reform by affirming that it followed a “democratic path” which began with “months of consultation”.

The claim of having followed a “democratic path” by the President, punctuated by regular reminders of “consultation” and “participation” mechanisms, is perplexing, as the political conduct of pension reform is obviously marked by the choice to reduce democratic debate to its strict minimum.

[This choice is highlighted when,] in the shadow of the pension reform, the citizens’ convention on the end of life, convened by the government, delivered its final opinion on April 2, 2023, after three months of deliberation.

Let us recall that the pension reform was itself the subject of a citizen consultation between 2018 and 2019, conducted under the leadership of a High Commission, which few commentators remember as it was ultimately disconnected from the reform adopted by the government. The avoidance of participation in the 2022 reform is therefore perfectly clear and represents a political choice.

Faced with the requests for participation expressed by the trade union organizations, the executive power does not simply present a refusal which would consist of delegitimizing these requests in the name of an electoral legitimacy superior to all others. On the contrary. Citizen participation has actually established itself over the past ten years as a veritable mantra among political and administrative elites, who consider it de facto as “their” tool. It is embodied, very officially, in the creation of a ministry in charge of “Citizen Participation” (Marc Fesneau, from 2018 to 2022) then “democratic renewal” (Oliver Veran, since 2022). Beyond the institutional facade, it is available in a myriad of participatory mechanisms, adopted in response to this slogan. However, these devices are often studied for their own sake. By dissecting them, or accompanying them, academics reflect on their scope, their promises and their limits. Recent cases of the Great National Debate or the Citizens’ Climate Convention have thus been considered as potential and imperfect democratic solutions, but which open paths for the future, under conditions that are debated by small circles of specialists, often in a speculative manner. However, this work does not include, in the same analysis, the establishment of these devices and the presidential practices of the political institutions which characterize the 5th Republic, which nevertheless continue to coexist. State participation must be understood as much by the mechanisms it authorizes as by those it refuses.

Filed under: Academia, Books, Elections, Participation, Press, Sortition |

In their essay in Against Sortition? The Problem with Citizens’ Assemblies, Cristina Lafont and Nadia Urbinati describe this kind of make-believe participation as “lottocratic technopulism: a toxic combination of political inequality and blind deference”.

LikeLike

[…] academic world continued to churn out the familiar arguments for and against sortition, with a side of AI. In this ongoing discussion, […]

LikeLike