It is only to be expected, and is generally acceptable, that a person or a group with decision-making power would use that power to shape the world in ways that seem “good” to them. In this sense being self-serving – trying to shape the world in ways that please the shaper – is benign. In the context of large scale politics this translates into the elites in society running society in ways which seem “good” to them. In this sense the elites being self-serving is benign (at least to the extent that the Iron Law of Oligarchy – i.e., the existence of a powerful political elite – is considered as a given).

It is only to be expected, and is generally acceptable, that a person or a group with decision-making power would use that power to shape the world in ways that seem “good” to them. In this sense being self-serving – trying to shape the world in ways that please the shaper – is benign. In the context of large scale politics this translates into the elites in society running society in ways which seem “good” to them. In this sense the elites being self-serving is benign (at least to the extent that the Iron Law of Oligarchy – i.e., the existence of a powerful political elite – is considered as a given).

The question is, of course, what do the elites see as “good”. As Western political thought presents things, elites tend to be, or at least over time tend to become, corrupt and see “good” as including, or even mainly as, the control of material goods by the elite and the control of the non-elite members of society by the elite. The “good” as the elite sees it is then in conflict with the “good” as rest of society sees it. Another, more recent, component of Western political thought is that elections are, through some mechanism (that is rarely examined very closely), an effective way – indeed, the only effective way – to prevent this corruption and to align the conceptions of the good of the elite with those of the rest of society.

It turns out that elections are not a particularly good mechanism to align the conceptions of the good of the elite and the non-elite population. On occasion the population largely feels that its good is promoted by the elected elite (e.g., the West in the 30 years after WWII and present day Russia). Much more often it does not. That’s a very problematic finding for the Western view of government – what may be termed as a Kuhnian anomaly.

But the situation in China presents an even more significant anomaly. In China there exists a very explicit mechanism of elite co-optation. The elite perpetuates itself by recruiting into its ranks those members of the public, and by promoting within its ranks members of the elite, that meet criteria set by the elite. This seems like the very definition of an insular self-selected group. According to Western thought, this should serve as a textbook example of a corrupting process which should pretty soon end with a complete divergence of the perceptions of the good between the elite and the rest of society. In fact, findings indicate the opposite – the Chinese see their government as serving them well.

Chinese political thought has it that getting the elite to conceive the good in a way that aligns with public’s conception can be achieved by proper recruitment procedures and by proper training. As long as China was poor and weak compared to the West it was easy to off-handedly dismiss this view as being either naive or manipulative or as being itself being part of an elite-specific conception of the good. With the astonishing rise of Chinese power it is now much more difficult to do so. (That said, the constant campaign to eliminate corruption in the Chinese system may indicate that the Chinese system is far from being without its difficulties.)

Another idea worth considering (which is rather along the lines of Western thinking) is that the tendency of elites to see the good in a way that is aligned with the popular ideas is linked to the situation of the society. According to this idea the elites are always corrupt and always have a narrow conception of the good. However, when the ruling elite is in competition with external (or internal) forces it needs to mobilize public support. It does so by ruling in a way that promotes the good as conceived by the public. Thus a superficial, instrumental alignment between the conceptions of the good is achieved temporarily. However, as soon as the elite feels secure it stops worrying about its perception by the public and pursues the elite-conceived narrow good. (According to this theory, the struggle with the powerful West can explain why present day Russian and Chinese elites serve the public good, while the competition with the Soviet block could explain the mid-20th century alignment of the good in Western societies.)

Sortition presents a way to bypass altogether the question of how to avoid diversion in the conception of the good between the political elite and the population. In a sortition-based system, unlike either the elections-based government or the co-optation-based government, the most powerful decision making bodies are not populated by an elite group but by normal members of the public. The conception of the good of the decision makers can thus be expected, by the application of the law of large numbers, to be aligned with the concpetion of the population.

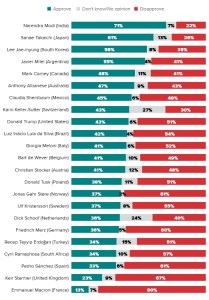

What is the source of the approval ratings posted? I have never seen Sheinbaum rated much below 70%. https://www.as-coa.org/articles/approval-tracker-mexicos-president-claudia-sheinbaum

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks for the data. The source for the chart is Morning Consult approval tracker https://pro.morningconsult.com/trackers/global-leader-approval. While Morning Consult are clearly ideologically strongly pro-business (big business are their clients), I have no opinion regarding the accuracy of their polls compared to other sources. It would be interesting to see how they explain the large discrepancy between their numbers for Sheinbaum and those of the local pollsters.

LikeLike