A new paper in the European Journal of Political Research (full text) provides data about popular support for allotted citizens’ assemblies in Western Europe. The countries surveyed were: Austria, Belgium, Denmark, Finland, France, Germany, Greece, Italy, Ireland, Netherlands, Norway, Portugal, Spain, Sweden, and the UK.

Public Support for Deliberative Citizens’ Assemblies Selected through Sortition: Evidence from 15 Countries

Jean-Benoit Pilet*, Damien Bol**, Davide Vittori*, and Emilien Paulis*

*Université libre de Bruxelles, Belgium

** King’s College London, United KingdomAbstract

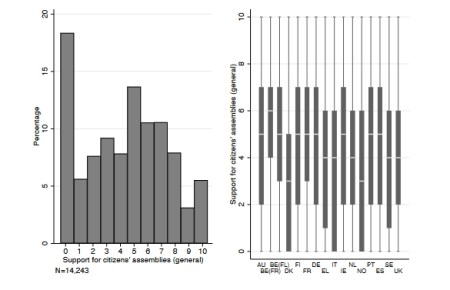

As representative democracy is increasingly criticized, a new institution is becoming popular among academics and practitioners: deliberative citizens’ assemblies. To evaluate whether these assemblies can deliver their promise of re-engaging the dissatisfied of representative politics, we explore who supports them and why. We build on a unique survey conducted with representative samples of 15 Western European countries and find, first, that the most supportive respondents are those who are less educated, have a low sense of political competence and an anti-elite sentiment. Thus, support does come from the dissatisfied. Second, we find that this support is for a part ‘outcome contingent’, in the sense that it changes with people’s expectations regarding the policy outcome from deliberative citizens’ assemblies. This second finding nuances the first one and suggests that while deliberative citizens’ assemblies convey some hope to re-engaged disengaged citizens, this is conditioned to the hope of a favourable outcome.

Despite emphasizing the “deliberative” label in the title of the paper, the question measuring support for allotted assemblies makes no mention of this obfuscatory term and instead focuses directly on decision-making power:

Overall, do you think it is a good idea to let a group of randomly-selected citizens make decisions instead of politicians on a scale going from 0 (very bad idea) to 10 (very good idea)?

The median response was 4.32, which is pretty impressive for such a radical idea. The chart below shows the distribution of responses. It is interesting to note that (if I read the chart correctly) the two countries with the lowest median support for the idea (3/10) are Denmark and Norway – the two Scandinavian countries in the survey. Those countries are among those with the highest level in the Western world of satisfaction with current government.

Filed under: Academia, Opinion polling, Press, Sortition | 15 Comments »

Micah Erfan is an economics freshman at the University of Houston. He

Micah Erfan is an economics freshman at the University of Houston. He

Setting up a large-scale democratic system presents a bootstrapping problem. It may be hoped that a large-scale democratic system is stable. That is, that once a democratic system is in place then it continues to function democratically and power does not spontaneously become concentrated leading to an oligarchical system. But even if this is the case, it would not imply that there is a realistic way to create a democratic system starting from an oligarchical one. Contrary to Western dogma, it is clear that large-scale democracy is not a spontaneously occurring phenomenon. Not only are some oligarchical system rather stable (with quite a few instances of the Western oligarchical system having survived for over 70 years), but, more importantly, once an oligarchical system destabilizes, often – in fact, historically, almost uniformly – the outcome is another oligarchical regime. The question then is how can the destabilization of an oligarchical regime, a phenomenon that seems to be happening now in various Western countries, become an opportunity for a transition to a democratic system.

Setting up a large-scale democratic system presents a bootstrapping problem. It may be hoped that a large-scale democratic system is stable. That is, that once a democratic system is in place then it continues to function democratically and power does not spontaneously become concentrated leading to an oligarchical system. But even if this is the case, it would not imply that there is a realistic way to create a democratic system starting from an oligarchical one. Contrary to Western dogma, it is clear that large-scale democracy is not a spontaneously occurring phenomenon. Not only are some oligarchical system rather stable (with quite a few instances of the Western oligarchical system having survived for over 70 years), but, more importantly, once an oligarchical system destabilizes, often – in fact, historically, almost uniformly – the outcome is another oligarchical regime. The question then is how can the destabilization of an oligarchical regime, a phenomenon that seems to be happening now in various Western countries, become an opportunity for a transition to a democratic system.