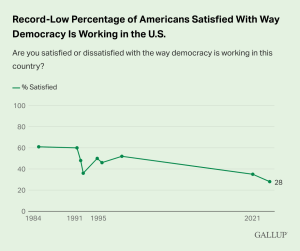

It is an unfortunate state of affairs that, despite the fact that proposals of empowering allotted bodies do enjoy significant popular support, most people are not mobilized into action by the idea of sortition. Much of that can no doubt be attributed to despair. There is no point in being politically attached to radical ideas since such attachment has insignificant impact on society and is bound to end in frustration, and quite possibly to being seen by friends and acquaintances as slightly unhinged.

Still, it is rather surprising that despite the unending contempt that many people heap on the existing electoralist system, or more accurately, on its outcomes and on those who act within the system, there is still a strong attachment to the idea of elections and aversion toward proposals at eliminating them altogether in favor of a sortition-based system. Of course, a long list of arguments against sortition is available, and they are endlessly regurgitated (often as if they were brand new) to justify the suspicion toward sortition. However, since all of these arguments are easily refuted, it is quite clear that the arguments are not the cause behind the aversion toward sortition, but rather that some underlying attitudes against sortition must be common, attitudes for which the arguments merely serve as rationalizations.

Continue reading

Filed under: Academia, Elections, Opinion polling, Sortition | 19 Comments »

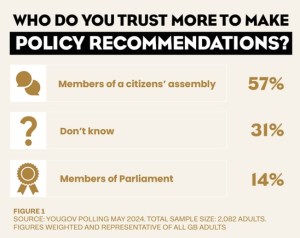

The first post regarding the recently released report by the UK think tank Demos proposing the use of allotted bodies as part of the British political system is

The first post regarding the recently released report by the UK think tank Demos proposing the use of allotted bodies as part of the British political system is

An argument against sortition that is

An argument against sortition that is