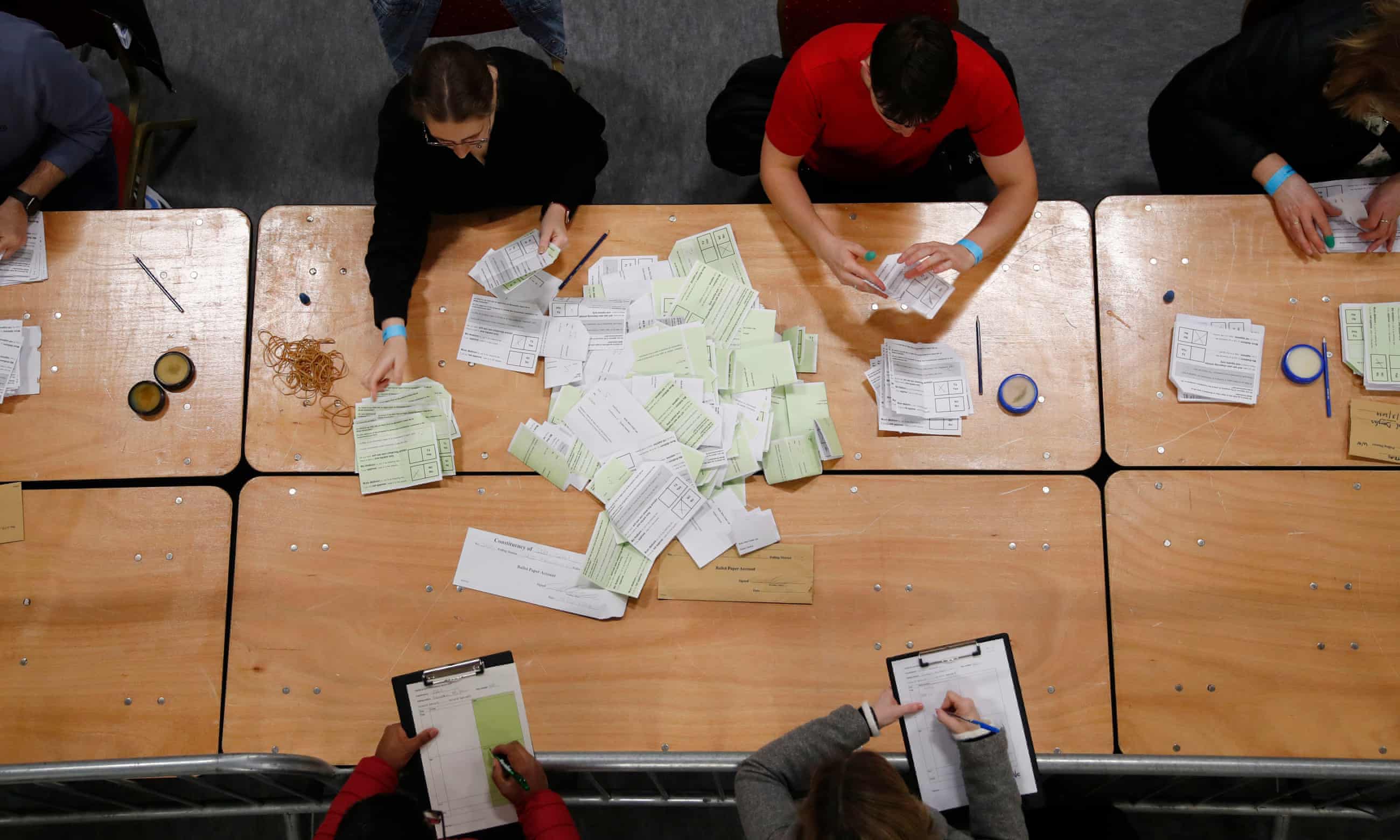

A referendum in Ireland on March 8 resulted in a “no” vote for constitutional changes. The rejected proposals were the product of a process involving an allotted citizen assembly. An article by Rory Carroll in the The Guardian offers an illuminating review of the aftermath of the failure of the proposed changes at the polls.

Irish referendum fiasco puts future of lauded citizens’ assemblies in doubt

Debates involving 99 randomly selected people were hailed as a model for the world, but some say faith has been eroded

When Ireland shattered its history of social conservatism by passing a 2015 referendum on same-sex marriage and a 2018 referendum on abortion, progressives credited its citizens’ assembly.

Ninety-nine randomly selected people, who are brought together to debate a specific issue, had weighed evidence from experts and issued policy recommendations that emboldened the political establishment, and voters, to make audacious leaps.

Governments and campaigners around the world hailed Ireland as a model for how to tackle divisive issues and a modern incarnation of the concept of deliberative democracy that dated back to ancient Athens.

Continue reading

Filed under: Applications, Press, Sortition | 21 Comments »

Carlos Acuña an attorney from El Centro, California, writes in the Calexico Chronicle:

Carlos Acuña an attorney from El Centro, California, writes in the Calexico Chronicle: