Bailey Flanigan, Paul Gölz, Anupam Gupta, and Ariel Procaccia, Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems (2020). https://arxiv.org/abs/2006.10498

Yoram recently drew our attention to this sortition paper which was highly ranked by the Google search engine. It’s interesting to see that engineers and computer scientists take the problem of self-selection bias more seriously than political theorists and sortition activists.

Abstract: Sortition is a political system in which decisions are made by panels of randomly selected citizens. The process for selecting a sortition panel is traditionally thought of as uniform sampling without replacement, which has strong fairness properties. In practice, however, sampling without replacement is not possible since only a fraction of agents is willing to participate in a panel when invited, and different demographic groups participate at different rates. In order to still produce panels whose composition resembles that of the population, we develop a sampling algorithm that restores close-to-equal representation probabilities for all agents while satisfying meaningful demographic quotas. As part of its input, our algorithm requires probabilities indicating how likely each volunteer in the pool was to participate. Since these participation probabilities are not directly observable, we show how to learn them, and demonstrate our approach using data on a real sortition panel combined with information on the general population in the form of publicly available survey data.

Citing statistics from the Sortition Foundation:

typically, only between 2 and 5% of citizens are willing to participate in the panel when contacted. Moreover, those who do participate exhibit self-selection bias, i.e., they are not representative of the population, but rather skew toward certain groups with certain features.

To address these issues, sortition practitioners introduce additional steps into the sampling process.

Continue readingFiled under: Academia, Applications, Sortition, Theory | 2 Comments »

Christopher Tripoulas

Christopher Tripoulas

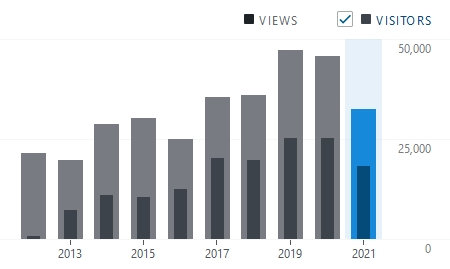

This is the yearly call for input for the year’s end review. As in previous years, I would like to have a post or two summarizing the ongoings here at Equality-by-Lot and notable sortition-related events over the passing year. Any input about what should be included is welcome – either through comments below or via email. You are invited to refresh your memory about the events of the passing year by browsing Equality-by-Lot’s archives.

This is the yearly call for input for the year’s end review. As in previous years, I would like to have a post or two summarizing the ongoings here at Equality-by-Lot and notable sortition-related events over the passing year. Any input about what should be included is welcome – either through comments below or via email. You are invited to refresh your memory about the events of the passing year by browsing Equality-by-Lot’s archives.