Glenn Greenwald is a former constitutional and civil rights lawyer and a prominent independent journalist, most famous for breaking the Snowden revelations about U.S. government surveillance.

In a recent segment on his show, Greenwald takes U.S. vice president J.D. Vance to task for claiming that U.S. supreme court is subverting the “democratic” will of the U.S. voters to deport all illegal residents from the country (as expressed in the election of Donald Trump to president) by putting up legal barriers to some deportation efforts implemented by the Trump administration. Greenwald rightly points out that Vance’s claim is obviously manipulative. The U.S. system has from the outset, deliberately and explicitly, set up various restrictions on what elected officials can do, and in particular legal challenges to executive policies have always been used, including, of course, by Republicans, to block popular policies.

When presented this way, all of this is the standard grist for the liberal mill. Politicians pretend to be concerned about the anti-majoritarian nature of mechanisms that they like to utilize in their favor when it suits them. “We”, good liberals who stand for civil rights and the rule of law, should be grateful that such mechanisms exist whether or not we support deporting illegal residents. Such mechanisms make sure that government is not despotic and that majorities do not oppress minorities. Specifically, a proper procedure for deporting illegal residents is already in place and is not in any way obstructed by the courts. We should all insist that this procedure is followed whether or not a majority of the voters wish to and thus it is good that the U.S. has anti-majoritarian procedures in place.

Continue reading

Filed under: Elections, Press | 1 Comment »

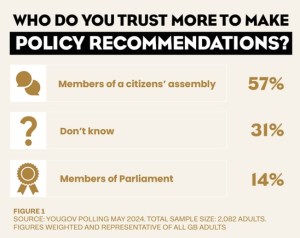

Clearly, “by the people” is a non-starter, so Nathan Gardels

Clearly, “by the people” is a non-starter, so Nathan Gardels

It appears that Mr. Smarty Pants Knows is a brief section in The Austin Chronicle which introduces readers to the lesser known words and expressions of the English language. The April 11th, 2025 of edition of this section

It appears that Mr. Smarty Pants Knows is a brief section in The Austin Chronicle which introduces readers to the lesser known words and expressions of the English language. The April 11th, 2025 of edition of this section