There’s a spectre haunting Europe … and the rest of the Western world. We have elaborate ‘diversity’ programs in good upper-middle-class places to prevent discrimination against all manner of minorities (and majorities like women). It’s a fine thing. But there’s a diversity challenge a little closer to home which is tearing the world apart. There’s a war on the less well educated.

They’re falling out of the economy in droves, being driven into marginal employment or out of the labour force. This is a vexing problem to solve economically if the electorate values rising incomes which it does. Because, as a rule, the less well educated are less productive.

Still, the less well educated are marginalised from polite society. Polite society even runs special newspapers for them. They’re called tabloids and they’re full of resentment and hate. And yes, a big reason they are the way they are is that the less well educated buy them. They’re also marginalised, except in stereotyped form from TV.

Then there are our institutions of governance. While less than 50 per cent of our population are university educated, over 90 per cent of our parliamentarians are. Something very similar would be going on down the chain of public and private governance down to local councils and private firms.

And I’m pretty confident that a lot of this is internalised even by those not well educated. The last working-class Prime Minister we’ve had in Australia was Ben Chifley who was turfed out of office by a silver-tongued barrister in 1949. Barrie Unsworth in NSW going down badly in his first election as NSW Premier despite seeming – at least to me to be doing quite a good job. But he sounded working class – because he was. I wonder if that was it?

The world is made by and for the upper middle class, those who’ve been to the right schools and gone to unis (preferably the right unis), to get on. The ancient Greeks had a political/legal principle of relevance here which is entirely absent from our political language. In addition to ‘παρρησία’ or ‘parrhesia‘ which is often translated as ‘freedom of speech’ but which also carries a connotation of the duty to speak the truth boldly for the community’s wellbeing even at your own cost (as Socrates did), they also had the concept of ‘ισηγορια’ or ‘isegoria‘ meaning equality of speech.1

In Australia Pauline Hanson’s One Nation represents the political system’s concession to isegoria – toxified as a protest party within a hostile political culture. My own support for a greater role for selection by lot in our democracy is to build more isegoria into our political system in a way that, I think there’s good evidence, can help us get to a much better politics and policy.

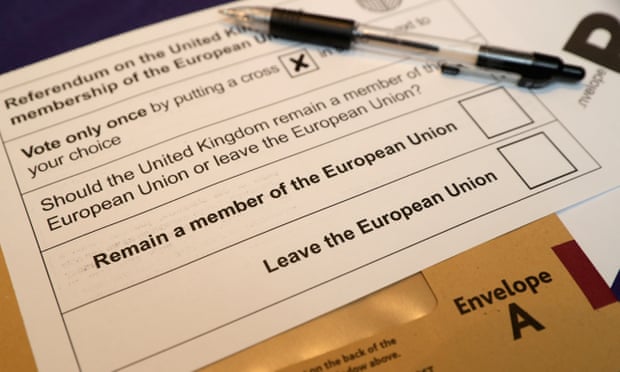

In any event, the big, most toxified political events illustrating these problems are, of course, Brexit and Trump – concrete political acts of transformative significance standing before illustrating the power of isegoria as rage. Continue reading

Filed under: Ballot measures, Deliberation, Elections, Participation, Proposals, Sortition | 3 Comments »

George Tridimas wrote to draw attention to the recent issue of the journal Homo Oeconomicus which has a set of comments (including one of his own) on a 2017 paper by the Swiss political economist

George Tridimas wrote to draw attention to the recent issue of the journal Homo Oeconomicus which has a set of comments (including one of his own) on a 2017 paper by the Swiss political economist  Not being British I hesitate to post this entry, but I am advised by an informed source that “this is DIRECTLY on point re your sortition cause, and from perhaps the most prominent public law academic of the past century.”

Not being British I hesitate to post this entry, but I am advised by an informed source that “this is DIRECTLY on point re your sortition cause, and from perhaps the most prominent public law academic of the past century.”