The following essay, dated June 14, was published in the online publication Contrepoints, which is published by the Liberaux organization.

The essay was written by Michel Quatrevalet, who is described thus:

Holding a B.Sc. in electrical engineering, Michel Quatrevalet spent 25 years in various operational positions in the industry. Over the last twenty years he has held various management and expert positions in multinational companies and in professional organizations in the areas of the environment and energy.

Original in French, my translation, corrections welcome.

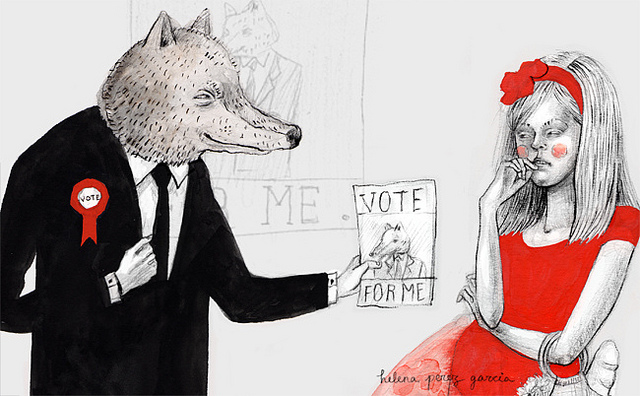

PPE: Sham participatory democracy in the energy domain

Ms. Jouanneau [sic, this probably refers to Chantal Jouanno, president of the CNDP, -YG] allotted 400 participants for a one day workshop on the multi-year energy plan (PPE). Have the conditions been met for this experiment in participatory democracy to work?

The debate around the PPE was “enriched” by an experiment in participatory democracy. Ms. Jouanneau allotted 400 participants for a one day workshop on the multi-year energy plan.

We don’t know much about the procedure, we don’t know the names of the 10 moderators, nor which documents were provided to the participants. During the written debates on the site of the Commision for Public Debate, several participants complained that some essential points of view were missing, such as the conclusions of the 2012 Percebois‑Grandil taskforce or the opinions of the Academy of Sciences and Technology.

The conclusions will be presented on June 29th, that is at the end of the consultation period, at which point it would be no longer possible to dispute them.

A sham process

Such activities of “allotted citizen panels” could be productive but only if three necessary conditions are met:

- An in-depth preparation of the participants that would make them sufficiently knowledgeable on the subject (energy is a highly technical subject),

- A detailed verification by an organization independent of the parties involved (including independence of the government) that the information provided is factual, complete and objective,

- A transparent process of nomination of the moderators and of the drawing up of the synthesis of the debates.

In reality, none of these conditions seems to have been observed. We can even fear the worst, reading the shamelessly biased report of the project’s management. The comments posted on the site of the debate were not heeded. Here are a few of them.

Continue reading

Filed under: Applications, Press, Sortition | 6 Comments »

Fintan O’Toole has

Fintan O’Toole has

David Van Reybrouck was recently

David Van Reybrouck was recently